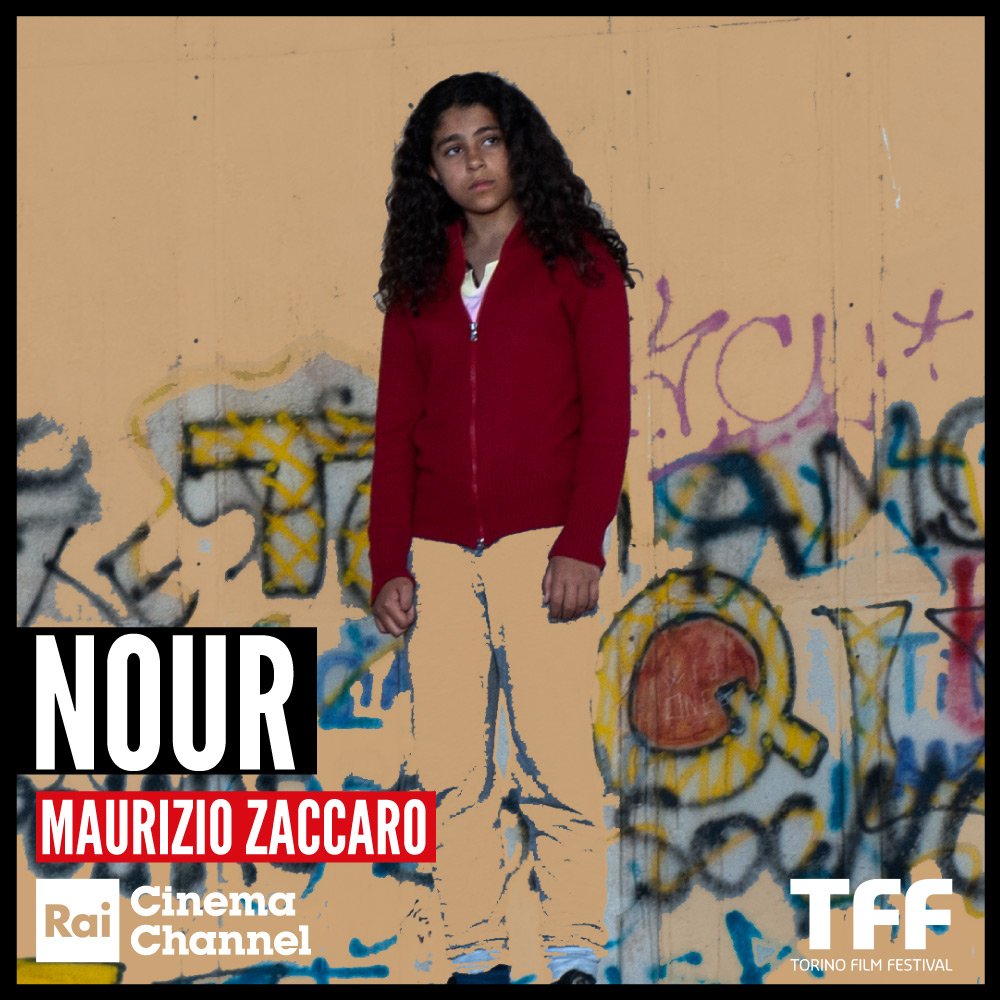

NOUR

Su RaiPlay, intenso e toccante Castellitto: un film che rimane dentro per sempre

30 Dicembre 2024 di Giusy Palombo

Sergio Castellitto in un film su RaiPlay che vale la pena non lasciarsi sfuggire: una visione che racconta un dramma attuale e difficile.

NOUR è integralmente visibile qui:

https://www.raiplay.it/video/2022/09/Nour-656efaf5-b22f-41e4-b34a-b6114efe379a.html

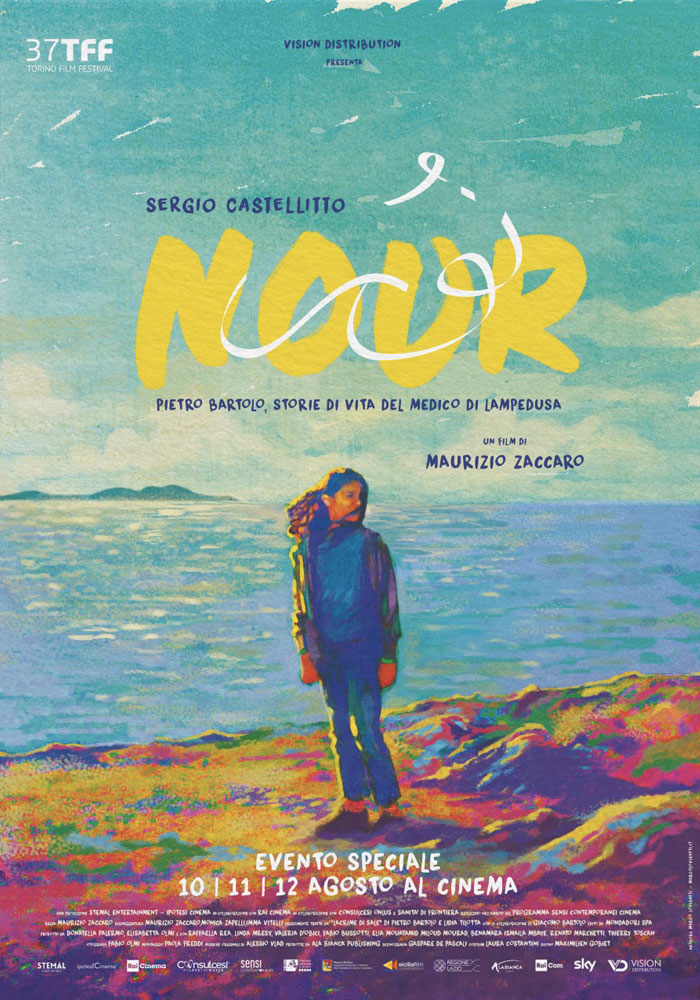

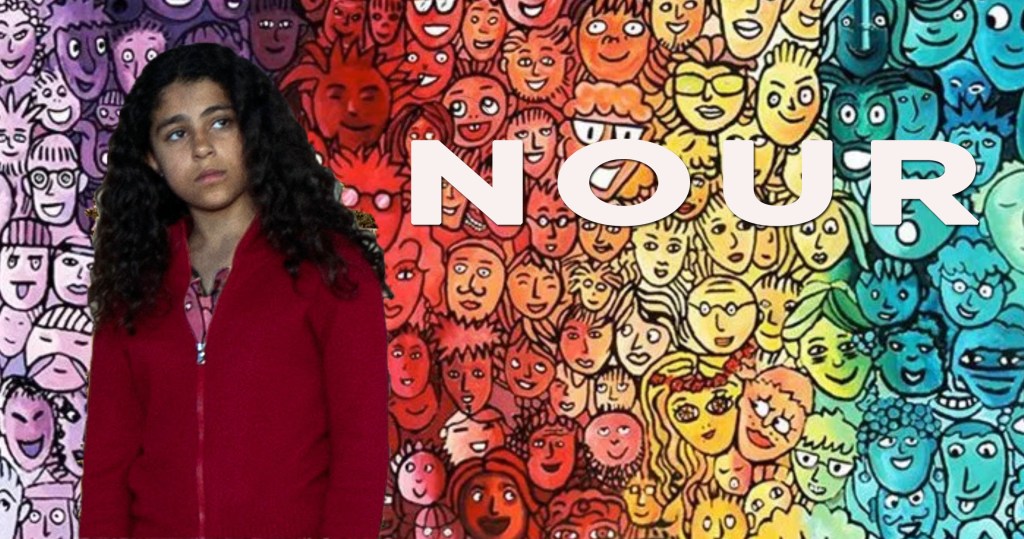

Maurizio Zaccaro ci consegna un’opera intensa e profondamente umana con Nour, un film che affronta una delle tragedie più attuali del nostro tempo: la crisi dei migranti. Con un cast guidato da un impeccabile Sergio Castellitto, il film è un racconto che non lascia indifferenti, capace di scuotere le coscienze e stimolare il dibattito. Una ragazzina siriana di nome Nour, arriva a Lampedusa da sola dopo un viaggio disperato che l’ha separata dalla madre, Fatima. Ad accoglierla è Pietro Bartolo (Sergio Castellitto), medico locale e figura simbolo di questa realtà. Bartolo non si limita a curare le ferite del corpo, ma si prende carico anche delle ferite dell’anima, decidendo di aiutare Nour a ritrovare sua madre.

Lampedusa, con le sue spiagge insidiose e i suoi centri di accoglienza sovraffollati, diventa il microcosmo di una tragedia globale. Tra disperazione, empatia e scelte difficili, il film intreccia le storie di chi arriva, di chi accoglie e di chi osserva da lontano, spesso con superficialità o pregiudizio. Questa pellicola brilla per la sua semplicità narrativa e per l’approccio privo di retorica. Maurizio Zaccaro evita di cadere in facili stereotipi, scegliendo di raccontare la storia attraverso una prospettiva intima, ma al contempo corale.

Stasera su RaiPlay, Sergio Castellitto in una delle sue migliori interpretazioni: un dramma che tutti dovrebbero conoscere

Sergio Castellitto regala una performance misurata e toccante, dando vita a un Pietro Bartolo che incarna l’umanità e la stanchezza di chi non può voltarsi dall’altra parte. Accanto a lui, Linda Mresy è straordinaria nel ruolo di Nour, un personaggio che sintetizza la fragilità e la resilienza di chi affronta l’indicibile. La regia di Zaccaro è essenziale, ma efficace, puntando sulla forza dei dialoghi e delle emozioni. Momenti di silenzio e primi piani intensi ci portano nel cuore di un dramma che non è solo della protagonista, ma di un intero sistema incapace di fornire soluzioni concrete.

Perché è una visione da scegliere questa sera sul piccolo schermo? Nour non è solo un film, ma un’esperienza emotiva e morale. La sua forza risiede nella capacità di dare voce a tutti i protagonisti di questa crisi, senza cedere al sensazionalismo. È un racconto che insegna empatia e che ci spinge a riflettere sul ruolo di ognuno di noi in un mondo sempre più interconnesso. Non perdere l’opportunità di vedere questa perla del cinema italiano, disponibile gratuitamente in streaming su RaiPlay. Prepara i fazzoletti e apri il cuore: Nour ti resterà dentro.

“Ho vissuto quasi tutta la vita a Lampedusa, la mia isola, che mi manca tantissimo. Come il mare e la mia famiglia allargata. Guardando il film ho ripensato ai miei dubbi, alle volte in cui, di fronte al corpo di un bambino morto in mare, pensavo di non farcela. Quante volte, in trent’anni, mi sono chiesto se avessi potuto fare di più. Ma mi è anche sembrato di aver fatto bene e sono orgoglioso”

“I have lived most of my life in Lampedusa, my island, which I miss so much. Like the sea and my extended family. Watching the film I thought back to my doubts, to the times when, faced with the body of a child who died at sea, I thought I couldn’t do it. How many times in 30 years I wondered if I could have done more. But I also felt I did well, and I am proud.”

Pietro Bartolo

24 luglio 2021: “Nour” si aggiudica il premio per il miglior film e il premio del pubblico al 2 ° MARETTIMO ITALIAN FILM FESTIVAL 2021

17 aprile 2021: “Nour” si aggiudica il prestigioso Premio del pubblico al 34° Film Festival di Bolzano/Bozen

L’UMANESIMO DI ZACCARO

In “Nour”, ultima fatica di un autore atipico come Maurizio Zaccaro, si percepisce tutta la sua viscerale passione per l’umanità, intesa come contributo poetico per la comprensione dei problemi sociali attraverso il cinema, ma anche come rivincita degli individui semplici ma tenaci come il medico di Lampedusa Pietro Bartolo che, nel corso di tre decadi, ha soccorso ben 350.000 disperati approdati al molo dell’isola. Con sensibilità e sapienza (quarant’anni spesi al fianco di Ermanno Olmi si vedono eccome) Zaccaro misura gli snodi narrativi, calibra la recitazione dei suoi attori, registra la consistenza dei suoi personaggi. Così facendo conferisce al suo lavoro una cifra “umanistica”. Il messaggio che ne scaturisce è ovviamente spinto verso l’idea che la pacifica coesistenza è non solo possibile ma necessaria, come lo scambio culturale tra diversi, fonte di reciproco arricchimento come sosteneva Seneca. Anche se l’epilogo strizza l’occhio a un “happy end” di stampo statunitense si esce dalla sala appagati e, forse, anche più sensibili al dolore del mondo. Non a caso Zaccaro ama citare, sia fra i dialoghi del film che nelle varie interviste, la frase incisa all’ingresso del palazzo di vetro dell’ONU, a New York: “Tutti i figli di Adamo formano un solo corpo, sono della stessa essenza. Quando il tempo affligge con il dolore una parte del corpo, anche le altre parti soffrono. Se tu non senti la pena degli altri non meriti di essere chiamato uomo” Parole di un filosofo persiano, Sa’di di Shiraz, pensate e scritte nel 1200.

In “Nour,” the latest effort by an atypical auteur like Maurizio Zaccaro, one can sense all his visceral passion for humanity, understood as a poetic contribution to the understanding of social problems through cinema, but also as the revenge of simple but tenacious individuals like the Lampedusa doctor Pietro Bartolo who, over the course of three decades, has rescued as many as 350,000 desperate people who landed at the island’s dock. With sensitivity and wisdom (forty years spent alongside Ermanno Olmi shows) Zaccaro measures the narrative junctures, calibrates the acting of his actors, and registers the consistency of his characters. In doing so, he gives his work a “humanistic” figure. The ensuing message is obviously driven toward the idea that peaceful coexistence is not only possible but necessary, like cultural exchange among different people, a source of mutual enrichment as Seneca argued. Although the epilogue winks at a U.S.-style “happy ending,” one leaves the theater fulfilled and, perhaps, even more sensitive to the world’s pain. It is no coincidence that Zaccaro likes to quote, both among the film’s dialogue and in the various interviews, the phrase engraved at the entrance to the UN’s glass building in New York:

“All of Adam’s children form one body, they are of the same essence. When time afflicts one part of the body with pain, the other parts also suffer. If you do not feel the pain of others you do not deserve to be called a man”.

Words of a Persian philosopher, Sa’di of Shiraz, thought and written in 1200.

Mirta Proesch

20 Settembre 2020 “Nour” conquista Marzamemi: miglior film e premio del pubblico

Cala il sipario sulla XX edizione del Festival internazionale Cinema di Frontiera

Comunicato stampa n. 8/2020

Marzamemi, Pachino 20 settembre 2020

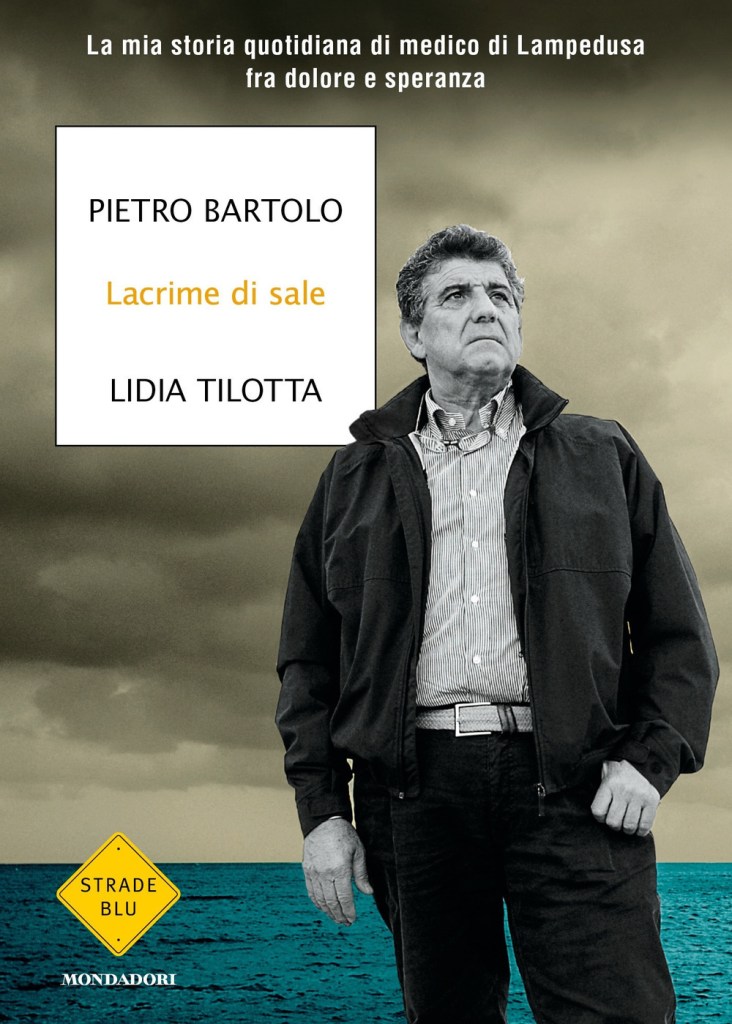

La storia di Nour, la ragazzina siriana sbarcata a Lampedusa alla ricerca della madre, ha conquistato Marzamemi. È il lungometraggio di Maurizio Zaccaro a fare incetta di premi alla XX edizione del Festival internazionale del Cinema di Frontiera. Il film tratto dal libro “Lacrime di sale”, scritto dal medico di Lampedusa Pietro Bartolo e Lidia Tilotta, ha vinto il Premio Speciale 2020 assegnato non da una giuria ma direttamente dal Festival e anche quello di gradimento decretato dal pubblico.

“Un film che per noi ha un significato particolare – ha dichiarato il direttore artistico Nello Correale – che rappresenta in pieno le motivazioni e la filosofia del nostro Festival. Nour ci ricorda che le frontiere, che cerchiamo di raccontare da 20 anni non sono solo geografiche, ma che quelle più difficili da superare sono interne, quelle che ci portiamo appresso. Il film di Zaccaro ci fa capire che, anche dopo la fine dell’emergenza sanitaria, rimarrà ancora da confrontarsi con un’ altra grande vicenda, che è quella dell’immigrazione. E la soluzione non la si potrà trovare in un vaccino, ma nella nostra coscienza e con la consapevolezza di affrontarla”.

The story of Nour, the little Syrian girl who landed in Lampedusa in search of her mother, has conquered Marzamemi. It is Maurizio Zaccaro’s feature film that racked up the awards at the 20th edition of the International Frontier Film Festival. The film based on the book “Tears of Salt,” written by Lampedusa doctor Pietro Bartolo and Lidia Tilotta, won the 2020 Special Prize awarded not by a jury but directly by the Festival, and also the approval prize decreed by the public.

“A film that has a special meaning for us,” said artistic director Nello Correale, ”which fully represents the motivations and philosophy of our Festival. Nour reminds us that the borders, which we have been trying to tell for 20 years, are not only geographical, but that the most difficult ones to overcome are internal, the ones we carry with us. Zaccaro’s film makes us realize that, even after the end of the health emergency, there will still remain to be confronted with ‘another big issue, which is that of immigration. And the solution will not be found in a vaccine, but in our consciousness and with the awareness to deal with it.”

_____________________________________________

Cinema in poltrona, da Parenti a Zaccaro

NOUR di Maurizio Zaccaro con Sergio Castellitto, Linda Mresy, Valeria D’Obici, Thierry Toscan, Raffaella Rea. Visibile su #iorestoinsala. A Lampedusa ogni giorno sbarcano migranti in fuga dalla miseria e dall’orrore. Ad accoglierli, tra gli altri, c’è il medico del posto, Pietro Bartolo che diventerà famoso grazie a “Fuocoammare” di Gianfranco Rosi. Nel film ha il volto di Sergio Castellitto e la sua storia si intreccia a quella della piccola Nour, una ragazzina siriana che ha perso il contatto con la madre. Il regista segue passo passo i suoi protagonisti in una storia di esemplare semplicità di stile.

NOUR by Maurizio Zaccaro with Sergio Castellitto, Linda Mresy, Valeria D’Obici, Thierry Toscan, Raffaella Rea. Viewable on #iorestoinsala. Migrants fleeing misery and horror land on Lampedusa every day. Welcoming them, among others, is local doctor Pietro Bartolo, who will become famous thanks to Gianfranco Rosi’s “Fuocoammare.” In the film he has the face of Sergio Castellitto and his story is intertwined with that of little Nour, a Syrian girl who has lost contact with her mother. The director follows his protagonists step by step in a story of exemplary simplicity of style.

GIORGIO GOSETTI . ANSA CULTURA – 09 dicembre 2020

INVIA UN MESSAGGIO A VISION DISTRIBUTION E RICHIEDI LA PROIEZIONE DI “NOUR” IN UNA SALA , O ARENA, DELLA TUA CITTA’.

https://www.visiondistribution.it/contatti/

Lo abbiamo conosciuto per il film Orso d’Oro “Fuocoammare”: lo chiamano “il medico di Lampedusa” e al pubblico si è svelato per la sua carica umana e capacità di raccontarci con semplicità e calore le storie di migranti appena sbarcati su quella piccola isola del Mediterraneo che è luogo di confine, avamposto dell’Europa e terra della speranza. Ma Pietro Bartolo dice sempre di essere uno dei tanti medici dediti a salvare le persone, proprio come i medici eroi di questi giorni in tempi di Covid.

A dare il volto a Bartolo nel film “Nour” di Maurizio Zaccaro c’è Sergio Castellitto, protagonista di questa storia commovente che vede al centro Nour, una bambina siriana di dieci anni che ha affrontato il viaggio per mare da sola e che ora vuole ritrovare sua madre. Bartolo-Castellitto, medico dell’isola, se ne prende cura e, un passo dopo l’altro, cerca di ricostruire non solo il passato della bambina, ma anche il suo presente e un nuovo futuro. Una storia vera e a lieto fine, che trae ispirazione dal libro “Lacrime di sale”, che raccoglie i ricordi eccezionali dello stesso Bartolo.

Il film che ha commosso la platea del Torino Film Festival, vincitore del premio del pubblico al Festival di Bastia, acclamato al festival internazionale di Montpellier, sarà distribuito da Vision – Universal.

“Nour” è una produzione Stemal Entertainment, Ipotesi Cinema in collaborazione con Rai Cinema, prodotto da Donatella Palermo, Elisabetta Olmi. Nel cast anche Raffaella Rea, Linda Mresy e Valeria D’Obici.

Il soggetto del film è di Pietro Bartolo, Diego De Silva, Maurizio Zaccaro, Monica Zapelli, liberamente tratto da “Lacrime di sale” di Pietro Bartolo e Lidia Tilotta con la collaborazione di Giacomo Bartolo Edito da Mondadori Spa, e la sceneggiatura di Monica Zapelli, Maurizio Zaccaro, Imma Vitelli. La fotografia è di Fabio Olmi, il montaggio di Paola Freddi, la scenografia di Gaspare De Pascali, i costumi di Laura Costantini, le musiche di Alessio Vlad (Ala Bianca Publishing).

We met him for the Golden Bear film “Fuocoammare”: they call him “the doctor from Lampedusa,” and to the public he has revealed himself for his human charge and ability to tell us with simplicity and warmth the stories of migrants who have just landed on that small Mediterranean island that is a borderland, an outpost of Europe and a land of hope. But Peter Bartolo always says he is one of many doctors dedicated to saving people, just like the hero doctors of these days in Covid times.

Giving Bartolo the face in Maurizio Zaccaro’s film “Nour” is Sergio Castellitto, the protagonist of this moving story that centers on Nour, a 10-year-old Syrian girl who faced the sea journey alone and now wants to find her mother. Bartolo-Castellitto, a doctor on the island, takes care of her and, one step at a time, tries to reconstruct not only the child’s past, but also her present and a new future. A true story with a happy ending, it draws inspiration from the book “Tears of Salt,” which collects the exceptional memories of Bartolo himself.

The film, which moved the audience at the Turin Film Festival, won the audience award at the Bastia Festival, and was acclaimed at the Montpellier International Film Festival, will be distributed by Vision – Universal.

“Nour” is a Stemal Entertainment, Ipotesi Cinema production in collaboration with Rai Cinema, produced by Donatella Palermo, Elisabetta Olmi. Raffaella Rea, Linda Mresy and Valeria D’Obici are also in the cast.

The subject of the film is by Pietro Bartolo, Diego De Silva, Maurizio Zaccaro, Monica Zapelli, loosely based on “Tears of Salt” by Pietro Bartolo and Lidia Tilotta with the collaboration of Giacomo Bartolo Published by Mondadori Spa, and the screenplay by Monica Zapelli, Maurizio Zaccaro, Imma Vitelli. Photography is by Fabio Olmi, editing by Paola Freddi, set design by Gaspare De Pascali, costumes by Laura Costantini, music by Alessio Vlad (Ala Bianca Publishing).

_____________________________________________

“NOUR”

OVVERO LA VITA A LAMPEDUSA

CASTELLITTO FA BARTOLO

di Michele Anselmi per SIAE

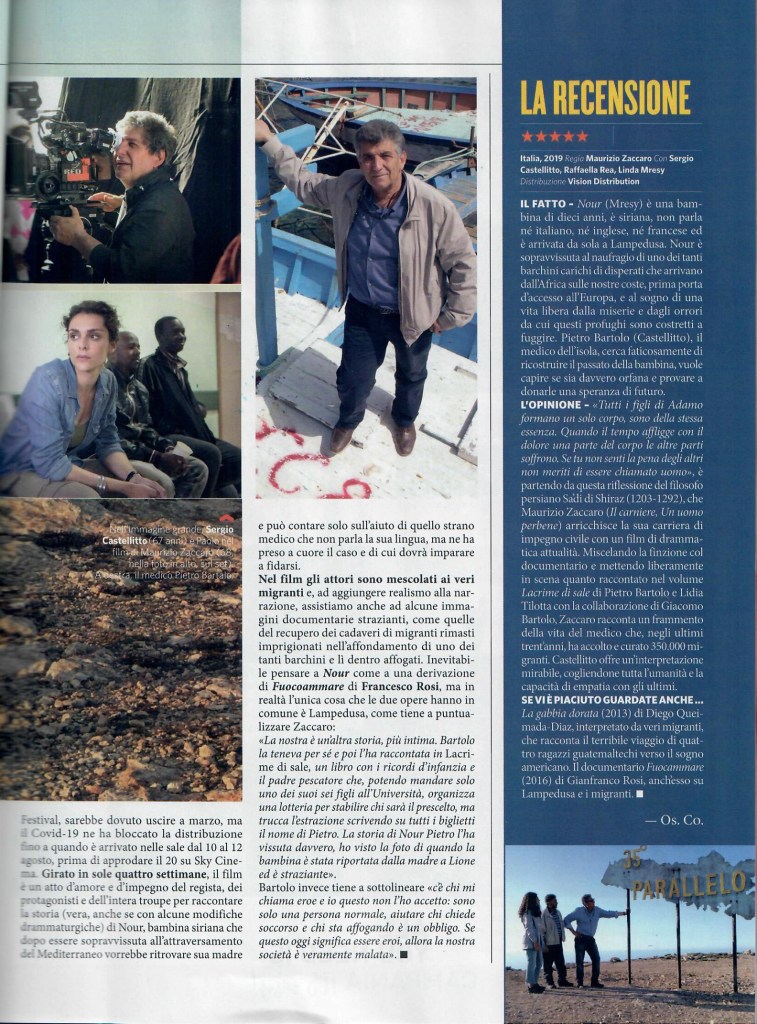

Il film è dedicato “a Ermanno”, cioè Ermanno Olmi, il regista scomparso nel 2018. Al tema dei migranti Olmi dedicò uno dei suoi ultimi film, “Il villaggio di cartone”, e non sorprende quindi che l’amico-allievo Maurizio Zaccaro, coinvolgendo due figli del cineasta bergamasco, la produttrice Elisabetta e il direttore della fotografia Fabio, riprenda il discorso, naturalmente in una chiave diversa. “Nour” esce nelle sale con Vision Distribution, come evento speciale, il 10, 11 e 12 agosto, poi sarà su Sky dal 20 di questo stesso mese. Consiglio di vederlo, perché è girato e recitato bene, dice cose ragionevoli su un argomento così delicato, anche fortemente “divisivo”, pesca nella realtà, nel senso che è una storia vera tratta dal libro “Lacrime di sale” scritto dal noto medico siciliano Pietro Bartolo, da pronunciarsi con l’accento sulla prima o.

E proprio Bartolo appare nel film incarnato da Sergio Castellitto, che ne restituisce un po’ l’accento siculo, i modi cordiali, il tratto paterno, forse anche una certa nobile rassegnazione di fronte alla tragedia epocale degli sbarchi. C’è una bella battuta, in sottofinale, che dice molto, se non tutto. Un vecchio di Lampedusa domanda al medico, vedendolo passeggiare sulla alte scogliere dell’isola: “Pietro che fai qui?”; e lui risponde allargando le braccia: “Aspetto”.

Il rischio era di farne un ritratto un po’ agiografico, ma Zaccaro si destreggia con cura, preferendo, coi suoi sceneggiatori, adottare il punto di vista di una bambina siriana, Nour al-Shabi, salvata nottetempo dalle acque oleose per via della nafta grazie a due turiste che guardano le stelle e a un pescatore che subito interviene. Gran massa di capelli, sguardo fiero, una consumata audiocassetta musicale a mo’ di amuleto e qualche soldo per sopravvivere, Nour non si fida di nessuno: ha perso il padre, ucciso da un colpo di fucile, durante la fuga, e la madre è rimasta a terra, in Libia, per orribile scelta dello scafista che ora si nasconde tra i naufraghi.

Bartolo cura i feriti e li rassicura, si occupa pietosamente dei morti, mette bocca sulla destinazione futura di quei poveretti, spesso forzando le procedure burocratiche. Sarà perché tutti gli vogliono bene a Lampedusa, anche i soldati e i carabinieri che ogni tanto chiudono un occhio. Il dilemma del film, anche il suo nucleo drammaturgico, è semplice: lasciare andare Nour nel centro di Palermo destinato ai bambini arrivati soli o “adottarla” per qualche giorno nella speranza di rintracciare la madre forse in viaggio verso qualche altra destinazione?

Il film sfodera un andamento quieto, registra i fatti, le incombenze sanitarie, elogia il lavoro svolto da Radio Delta Lampedusa, descrive la vita nel centro di prima d’accoglienza, i battibecchi amichevoli col prete locale, introduce il personaggio della bella giornalista free-lance approdata sull’isola insieme al suo fotografo, un po’ cinico, un tempo di sinistra, ormai forse leghista. Qua e là i dialoghi suonano un po’ troppo “scritti”, programmatici, pure nella ripartizione delle diverse posizioni in campo, ma emerge in generale un racconto riuscito, non retorico, che fa i conti con il cupo destinato di quei derelitti che, per dirla con Bartolo, “vivono per pagarsi la morte”.

Castellitto, magari un troppo ben vestito, si immerge con sensibilità e convinzione nel ruolo non facile di Bartolo, il medico buono; mentre il versante femminile è servito da Linda Mresy, Raffaella Rea e Valeria D’Obici, rispettivamente nei ruoli della piccola Nour, della giornalista e della mediatrice culturale.

Solo un’annotazione. A un certo punto Bartolo scandisce: “Destra, sinistra… Io non faccio politica”. Però oggi fa politica, eccome, essendo europarlamentare eletto nelle liste del Pd.

The film is dedicated “to Ermanno,” meaning Ermanno Olmi, the director who passed away in 2018. To the theme of migrants Olmi dedicated one of his last films, “Il villaggio di cartone,” and so it is not surprising that friend-pupil Maurizio Zaccaro, involving two of the Bergamasque filmmaker’s children, producer Elisabetta and director of photography Fabio, picks up the discourse, of course in a different key. “Nour” comes out in theaters with Vision Distribution, as a special event, on August 10, 11 and 12, then it will be on Sky from the 20th of this same month. I recommend seeing it, because it is well shot and acted, says reasonable things about such a sensitive, even strongly “divisive” topic, draws in reality, in the sense that it is a true story from the book “Tears of Salt” written by the well-known Sicilian doctor Pietro Bartolo, to be pronounced with the accent on the first o.

And it is precisely Bartolo who appears in the film embodied by Sergio Castellitto, who restores a bit of his Sicilian accent, his friendly manner, his fatherly trait, perhaps even a certain noble resignation in the face of the momentous tragedy of the landings. There is a good line, in the sub-final, that says much, if not everything. An old man from Lampedusa asks the doctor, seeing him walking on the island’s high cliffs, “Pietro what are you doing here?”; and he replies, spreading his arms wide, “Waiting.”

The risk was to make it a somewhat hagiographic portrait, but Zaccaro juggles it carefully, preferring, with his screenwriters, to adopt the point of view of a little Syrian girl, Nour al-Shabi, rescued overnight from oily waters by naphtha thanks to two stargazing tourists and a fisherman who immediately intervenes. A great mass of hair, a proud gaze, a worn-out music audiotape as an amulet, and some money to survive, Nour trusts no one: she lost her father, killed by a gunshot, during the escape, and her mother remained ashore in Libya by the horrible choice of the boatman who now hides among the castaways.

Bartolo treats the wounded and reassures them, pitifully takes care of the dead, and puts his mouth on the future destination of those poor people, often forcing bureaucratic procedures. It must be because everyone loves him in Lampedusa, even the soldiers and carabinieri who occasionally turn a blind eye. The film’s dilemma, even its dramaturgical core, is simple: let Nour go to the Palermo center intended for children who arrived alone or “adopt” her for a few days in the hope of tracking down her mother perhaps on her way to some other destination?

The film shows off a quiet pace, recording the facts, the sanitary tasks, praising the work done by Radio Delta Lampedusa, describing life in the first reception center, the friendly squabbles with the local priest, introducing the character of the beautiful free-lance journalist who landed on the island together with her photographer, a bit cynical, once a leftist, now perhaps a leghist. Here and there the dialogues sound a bit too “scripted,” programmatic, even in the distribution of the different positions in the field, but a successful, non-rhetorical narrative emerges in general, one that reckons with the grim destined of those derelicts who, in Bartolo’s words, “live to pay their own way.”

Castellitto, perhaps an overly well-dressed, plunges with sensitivity and conviction into the not-so-easy role of Bartolo, the good doctor; while the female side is served by Linda Mresy, Raffaella Rea and Valeria D’Obici, respectively in the roles of little Nour, journalist and cultural mediator.

Just a note. At one point Bartolo sounds out, “Right, left… I don’t do politics.” But today he does politics, and how, being a Europarliamentarian elected in the lists of the Democratic Party.

MAURIZIO ZACCARO – NOTA DI REGIA

“NOUR” racconta la follia di un mondo che si vuole sempre più diviso fra nord e sud, nel tentativo di rendere l’Europa una fortezza inespugnabile. Spostando il punto di attenzione dal racconto nello sguardo di chi trova la salvezza nell’ultimo (o nel primo, dipende dai punti di vista) lembo di terra italiana, la storia di Nour Al Shabi (Linda Mresy) bambina siriana di undici anni arrivata senza genitori a Lampedusa, diventa così una sorta di “Axis Mundi” attorno al quale si collegano il cielo, la terra e gli inferi, in questo caso rappresentati dal mare che, dal 1993 ad oggi, ha inghiottito più di 35.000 vite umane. Una strategia narrativa che capovolge il rapporto con lo spettatore: non è chi è seduto in sala a guardare le immagini ma sono le immagini a guardare l’indifferenza.

Non mettiamoci quindi a fare solo della sterile politica, a spaccare il capello in quattro, a discettare di cinema o fiction-tv standosene bene al sicuro davanti al proprio pc, magari protetti da una porta blindata. Il mondo deve essere scosso dalle fondamenta perché tutti sappiano quello che sta accadendo nel Mediterraneo Centrale. Non bastano le news dei tg. Non bastano i talk show. Non basta l’obolo all’Ong che ci è più simpatica, Occorre invece che la gente capisca davvero la sofferenza degli altri. L’Unione Europea (se di vera Unione si tratta) deve intervenire radicalmente, trovare la forza di compiere sacrifici, magari anche di essere impopolare, altrimenti tutto continuerà così, giorno dopo giorno, gommone dopo gommone ribaltato in acqua. Quello che sta succedendo non ha precedenti nella storia dell’umanità e a tutto questo dobbiamo reagire secondo modalità altrettanto inedite, dare risposte mai fornite prima. E’ così difficile?

Nel lontano 1200, il filosofo persiano Sa’di di Shiraz ha scritto: “Tutti i figli di Adamo formano un solo corpo, sono della stessa essenza. Quando il tempo affligge con il dolore una parte del corpo, anche le altre parti soffrono. Se tu non senti la pena degli altri non meriti di essere chiamato uomo”

Ecco, chissà che un piccolo film come Nour possa servire a farci tornare umani, consapevoli che siamo tutti figli di Adamo, appunto. Lo spero. Intanto, se volete, fate il passaparola, dite che questo film esiste, chiedetelo in programmazione ovunque voi siate, nei cinema come nelle scuole e, qualora lo vogliate, quel giorno sarò con voi, magari insieme a Pietro Bartolo, il medico di Lampedusa che durante i suoi trent’anni di lavoro al poliambulatorio dell’isola ha soccorso più di 350.000 esseri umani: donne, uomini e bambini approdati miracolosamente al molo Favaloro.

Maurizio Zaccaro – dicembre 2019

“NOUR” recounts the madness of a world that wants to increasingly divide north and south in an attempt to make Europe an impregnable fortress. Shifting the point of attention from the narrative into the gaze of those who find salvation in the last (or first, depending on the point of view) strip of Italian land, the story of Nour Al Shabi (Linda Mresy) an eleven-year-old Syrian girl who arrived without parents in Lampedusa, thus becomes a sort of “Axis Mundi” around which the sky, the earth and the underworld are connected, in this case represented by the sea that, since 1993 to date, has swallowed more than 35,000 lives. This is a narrative strategy that reverses the relationship with the viewer: it is not those sitting in the theater who watch the images but the images who watch the indifference.

So let’s not just engage in sterile politics, splitting hairs, and discussing movies or TV dramas while sitting safely in front of one’s PC, perhaps protected by a security door. The world must be shaken from the ground up for everyone to know what is happening in the Central Mediterranean. The news in the news is not enough. Talk shows are not enough. The obolus to the NGO we like best is not enough, Instead, it is necessary for people to really understand the suffering of others. The European Union (if it is a real Union) must intervene radically, find the strength to make sacrifices, maybe even to be unpopular, otherwise everything will continue like this, day after day, dinghy after dinghy capsized in the water. What is happening is unprecedented in the history of mankind, and to all this we must react in ways that are equally unprecedented, give answers that have never been given before. Is this so difficult?

Back in the 1200s, the Persian philosopher Sa’di of Shiraz wrote, “All the sons of Adam form one body; they are of the same essence. When time afflicts one part of the body with pain, the other parts also suffer. If you do not feel the pain of others, you do not deserve to be called a man.”

Here, who knows, a little film like Nour may serve to make us human again, aware that we are all Adam’s children, precisely. I hope so. In the meantime, if you want, spread the word, say that this film exists, ask for it to be shown wherever you are, in cinemas as well as in schools, and, should you wish, I will be with you that day, perhaps together with Pietro Bartolo, the Lampedusa doctor who during his 30 years of work at the island’s polyclinic has rescued more than 350,000 human beings: women, men and children who miraculously landed at the Favaloro pier.

_____________________________________________

Il placido guardar le stelle di due turiste in barca viene interrotto da grida d’aiuto. La notte calma, poetica d’una vacanza nel Mediterraneo, nel lembo più a Sud di terra italiana, incontra la tenebra fredda, disperata, in cui altra umanità si trova prigioniera. È così, con questo contatto inevitabile, con questi due mondi uno nell’altro, volti diversi dello stesso mare, che si apre Nour, il film di Maurizio Zaccaro ispirato al libro Lacrime di sale, scritto — insieme alla giornalista Lidia Tilotta — da Pietro Bartolo: il medico, oggi europarlamentare, che per circa trent’anni è stato direttore del poliambulatorio di Lampedusa e responsabile delle prime visite ai migranti sbarcati sull’isola.

La sua storia, la sua incoraggiante, esemplare, ostinazione lavorativa, visceralmente legata a una radicale idea di umanità, sono affidate a Sergio Castellitto, che con un delicato accento siciliano e un trasporto visibile in ogni sequenza, sostiene e accompagna questo film — uscito nelle sale dal 10, al 12 agosto e dal 20 visibile su Sky — nel delicato compito di rendere più tangibile, vivo, necessariamente doloroso a ogni cuore distratto, il fenomeno delle migrazioni, con le storie, spesso tragiche, di quegli esseri umani che a un certo punto del film guardano in macchina pronunciando nome e provenienza direttamente allo spettatore: per ricordargli che sono persone con dignità e identità, anche se può essergli rimasto solo il «corpo» e la «fame», dice Bartolo, e la «paura» dopo la costrizione «a vivere pagandosi la morte».

L’esperienza del medico è versata in questo film dedicato a Ermanno Olmi — di cui Zaccaro è stato amico e collaboratore — che ha il suo nucleo centrale nella storia di Nour, una ragazzina siriana di 11 anni, la quale, separata a forza dalla madre in Libia, poco prima di salire su un barcone, viene aiutata proprio da Bartolo a ritrovarla. È a lieto fine, la vicenda di Nour, ed è un racconto di speranza più che una trama televisiva; è una storia vera frutto della tenacia del figlio di un pescatore: l’unico, tra sette fratelli, a poter studiare e diventare medico.

Da qui un «peso», e una «responsabilità», ricorda il protagonista, quei muscoli dell’anima per saltare sopra ogni forma di sufficienza, per andare, se serve a costruire il bene, oltre il protocollo: aiutando quella donna che deve volare a Palermo per partorire a non separarsi dai suoi cari, e più in generale a vedere una vita da proteggere dietro le facce smarrite e le sagome provate, ammassate tra le coperte termiche. È una storia, quella di Nour, la cui luce offre ossigeno per rimanere in apnea tra gli abissi di altre storie, come quella di Hassan — racconta sempre il film — che ha perso il suo bambino nella traversata, e a Bartolo tocca l’amaro compito di comunicargli il ritrovamento, dopo averlo riconosciuto coi pantaloncini rossi dentro un sacco numerato, il 209, in mezzo ad altri corpi senza vita. «Apro gli occhi e lo vedo, chiudo gli occhi e lo vedo», confessa a sua moglie parlando di questa storia tragica, accolta, come tutte le altre, senza tirarsi indietro, con quella sofferenza che non gli impedisce di dire, alla fine del film, «aspetto», nella sua opera di soccorritore, da abitante di quell’isola che ha sempre considerato «porto aperto» e che definisce «alta» e «fiera» per la sua capacità di abbracciare il bisognoso nonostante i segni portati dentro per il dolore visto, per la morte toccata tante volte.

Anzi proprio per questo è necessario esserci. «Dicono che ci si abitua — spiega il medico in un’altra sequenza — ma non ci si abitua mai». Lo stesso ha scelto di spendere, di dedicare — non di sprecare come qualcuno vuole fargli credere nel film — la sua vita lì, per ciò che è «giusto», e la sua testimonianza è il motore con cui Nour si propone di penetrare la pelle dello spettatore meglio dei fiumi di notizie con i loro numeri freddi. Lo fa scegliendo la strada dell’asciuttezza, della semplicità narrativa al servizio della sostanza, di una magrezza robusta e non impermeabile a immagini e parole importanti, a pensieri come quello che Bartolo esprime dialogando con un fotografo perplesso, impaurito, che si chiede dove finisca tutta quella gente dopo che il medico l’ha curata.

«Mi piace immaginare l’umanità come un unico corpo — spiega il dottore di Lampedusa — se ti fa male un braccio tutto il corpo sta male. Se una parte dell’umanità soffre, tutto il resto dell’umanità non può stare sereno». È una frase che riprende i versi antichi del poeta persiano Saadi di Chiraz, leggibili anche sul palazzo di vetro dell’Onu. È piena di bellezza perché parla di umanità prima che di qualsiasi altra cosa e di un unico paese, di una relazione e di uno scambio, di una solidarietà tra tutti gli uomini che vale il beneficio di ognuno. È un incoraggiamento, anche, a quella giornalista che arrivata sull’isola, di fronte alla tragedia si chiede: «Scriviamo articoli su articoli, non so se serve a qualcosa». Serve a non voltarsi dall’altra parte perché «l’orrore ha bisogno di testimoni» risponde il medico appena uscito da un’altra dolorosa ispezione cadaverica. «Fai bene a dirlo», consiglia anche al giovane che parla dal microfono di Radio Delta Lampedusa, anche se non sono in tanti ad ascoltare, anche se facilmente quel che accade provoca rabbia e frustrazione, e la triste forza degli eventi è superiore all’impegno di uomini sensibili e combattivi.

Anche se un gruppo di tombe senza nome, in uno spazio ricavato dentro al cimitero, ha bisogno di un cartello che ricordi di non gettarvi sopra i rifiuti: la necessità di quella scritta è un sottile indicatore della quantità enorme di lavoro da fare, e il primo passo da compiere è una stretta di mano tra uomini come quella che Pietro Bartolo allunga al sacerdote dopo le loro piccole incomprensioni e discussioni per le richieste continue del medico. È una unione necessaria a combattere quella «globalizzazione dell’indifferenza» in cui siamo «caduti», disse Papa Francesco nel suo viaggio a Lampedusa nel 2013. E il cinema, con un paradigma etico e di perseveranza come quello di Pietro Bartolo, può offrire occhi per far lavorare dentro di noi la verità, per rendenderci meno «insensibili alle grida degli altri», disse ancora Bergoglio nell’omelia sull’isola, esprimendo, in quella sua visita, già tutta la sua profonda compassione per ogni vita rischiosamente in fuga da situazioni difficili.

di Edoardo Zaccagnini – L’Osservatore Romano – 18 agosto 2020

The placid stargazing of two tourists on a boat is interrupted by cries for help. The calm, poetic night of a vacation in the Mediterranean, in the southernmost strip of Italian land, meets the cold, desperate darkness in which other humanity finds itself imprisoned. It is thus, with this inevitable contact, with these two worlds one in the other, different faces of the same sea, that Nour opens, Maurizio Zaccaro’s film inspired by the book Tears of Salt, written – together with journalist Lidia Tilotta – by Pietro Bartolo: the doctor, now a member of the European Parliament, who for about thirty years was director of the Lampedusa polyclinic and responsible for the first visits to migrants who landed on the island.

His story, his encouraging, exemplary, working obstinacy, viscerally linked to a radical idea of humanity, is entrusted to Sergio Castellitto, who, with a delicate Sicilian accent and a transport visible in every sequence, supports and accompanies this film-released in theaters from Aug. 10, to Aug. 12 and from the 20th visible on Sky – in the delicate task of making more tangible, alive, necessarily painful to any distracted heart, the phenomenon of migration, with the stories, often tragic, of those human beings who at one point in the film look into the camera pronouncing name and origin directly to the viewer: to remind them that they are people with dignity and identity, even though they may be left with only their “bodies” and “hunger,” Bartolo says, and “fear” after being forced “to live by paying for their own deaths.”

The doctor’s experience is poured into this film dedicated to Ermanno Olmi-with whom Zaccaro was a friend and collaborator-which has its core in the story of Nour, an 11-year-old Syrian girl who, forcibly separated from her mother in Libya just before boarding a barge, is helped by Bartolo himself to find her. It has a happy ending, Nour’s story, and it is a tale of hope rather than a TV storyline; it is a true story borne out of the tenacity of a fisherman’s son: the only one, among seven siblings, who was able to study and become a doctor.

Hence a “burden,” and a “responsibility,” the protagonist recalls, those muscles of the soul to leap above all forms of sufficiency, to go, if it serves to build good, beyond protocol: helping that woman who must fly to Palermo to give birth not to be separated from her loved ones, and more generally to see a life to be protected behind the lost faces and tried silhouettes crammed between thermal blankets.

. It is a story, that of Nour, whose light offers oxygen to remain apnea among the abysses of other stories, such as that of Hassan – the film always recounts – who lost his child in the crossing, and Bartolo has the bitter task of informing him of the finding, after recognizing him in his red shorts inside a numbered sack, 209, among other lifeless bodies. “I open my eyes and I see him, I close my eyes and I see him,” he confesses to his wife, speaking of this tragic story, welcomed, like all the others, without backing down, with that suffering that does not prevent him from saying, at the end of the film, ‘I wait,’ in his work as a rescuer, as an inhabitant of that island that he has always considered an ‘open port’ and that he calls ‘high’ and ‘proud’ for its ability to embrace the needy despite the marks carried inside for the pain seen, for the death touched so many times.

Indeed, for this very reason it is necessary to be there. “They say you get used to it,” the doctor explains in another sequence, ”but you never get used to it. He himself has chosen to spend, to devote-not waste as some would have him believe in the film-his life there, for what is “right,” and his testimony is the engine by which Nour sets out to penetrate the viewer’s skin better than the rivers of news with their cold numbers.

He does so by choosing the path of dryness, of narrative simplicity in the service of substance, of a robust leanness that is not impervious to important images and words, to thoughts like the one Bartolo expresses in dialogue with a perplexed, frightened photographer who wonders where all those people end up after the doctor treats them.

“I like to imagine humanity as one body,” the Lampedusa doctor explains, ”if one arm hurts, the whole body is sick. If one part of humanity suffers, all the rest of humanity cannot be serene.” It is a phrase that echoes the ancient verses of the Persian poet Saadi of Chiraz, which can also be read on the UN’s glass building. It is full of beauty because it speaks of humanity before anything else and of one country, one relationship and one exchange, one solidarity among all people worth the benefit of each. It is an encouragement, too, to that journalist who arrived on the island, faced with tragedy and wondered, “We write article after article, I don’t know if it serves any purpose.” It helps not to turn away because “horror needs witnesses,” replies the doctor who has just emerged from another painful cadaveric inspection.

“You do well to say it,” he also advises the young man speaking from the microphone of Radio Delta Lampedusa, even if not many are listening, even if easily what happens provokes anger and frustration, and the sad force of events is greater than the commitment of sensitive and combative men.

Even if a group of unmarked graves, in a space carved out inside the cemetery, needs a sign reminding them not to throw garbage on them: the need for that sign is a subtle indicator of the enormous amount of work to be done, and the first step to be taken is a handshake between men like the one Pietro Bartolo extends to the priest after their petty misunderstandings and arguments over the doctor’s constant demands. It is a necessary union to combat that “globalization of indifference” into which we have “fallen,” Pope Francis said on his trip to Lampedusa in 2013. And cinema, with a paradigm of ethics and perseverance such as that of Peter Bartolo, can offer eyes to make the truth work within us, to make us less “insensitive to the cries of others,” Bergoglio said again in his homily on the island, already expressing, in that visit, all his deep compassion for every life riskingly fleeing from difficult situations.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

NOUR In attesa e in solitudine

Dialogo con Maurizio Zaccaro

A cura di Barbara Massimilla – 27 agosto 2020

Nel film Nour la separazione tra una madre e una figlia, il loro perdersi di vista durante il viaggio migratorio, è una tragedia nella tragedia, quella che da trent’anni affligge persone costrette a fuggire da guerre, povertà, carestie, a lasciare i propri luoghi d’origine alla ricerca di una vita migliore. Vorrei iniziare con una citazione a te cara di un mistico persiano, una frase di Sa’di di Shiraz sulla sensibilità che ogni uomo dovrebbe sviluppare predisponendosi interiormente a percepire le pene, le sofferenze dell’altro.

Si tratta di una sua frase del 1200 ed esprime una visione del mondo molto particolare: “Tutti i figli di Adamo formano un solo corpo, sono della stessa essenza. Quando il tempo affligge con il dolore una parte del corpo, anche le altre parti soffrono. Se tu non senti la pena degli altri non meriti di essere chiamato uomo”. Se non percepisci le pene dell’altro alla fine non puoi nemmeno essere definito uomo.

Pensavo da un punto di vista psicoanalitico al processo d’immedesimazione che si attiva nel compenetrarsi nell’ascolto dell’altro, entrare dall’interno di una relazione profonda nella vita e nel mondo dell’altro, da questo punto di vista fare proprie anche quelle che sono le sue ferite e le sue pene per trasformarle.

Non è casuale che questa frase sia incisa in più lingue sul muro d’ingresso del palazzo delle Nazioni Unite a New York. Sa’di di Shiraz era un Sufi, apparterrebbe al passato, eppure con il trascorrere dei secoli sembrerebbe che l’umanità sia rimasta immobile su questa questione, che debba ancora riflettere sull’essenza di questo messaggio, sulle problematiche ad esso connesse.

Si parla tanto senza agire incisivamente, il mondo contemporaneo soffre per una mancanza di azioni vere, equilibrate, risolutive, che rispecchino un’elaborazione profonda sulla condizione umana e sul suo destino. Con Pietro Bartolo, medico di Lampedusa, hai descritto una figura simbolica per certi versi archetipica. Bartolo così magistralmente interpretato da Castellitto ha il sapore di personaggi etici e antichi, propone un modello di esistenza che va difeso poiché, infondo, ai nostri giorni è l’unico che dà un senso autentico alla vita, alla convivenza.

Pietro Bartolo è un medico che a Lampedusa ha fatto in pieno il suo lavoro, prima di diventare due anni fa europarlamentare. Non ha mai voluto essere un eroe, anche se ha soccorso e curato 350.000 esseri umani, ha sostenuto sempre di aver fatto semplicemente il suo dovere di medico. Si esprime con parole schiette, dirette. Si percepisce il suo essersi sentito solo, difatti intorno a lui si è sempre respirato un vuoto totale DA PARTE DELLE ISTITUZIONI. Ha portato avanti il suo impegno professionale e umano in solitudine. Da solo su un molo ha accolto una moltitudine di solitudini.

Il molo di Lampedusa in passato era di pietra senza nessun riparo dal sole, adesso è una lunga striscia d’asfalto protesa nel mare sul quale Bartolo ha fatto costruire dei gazebo per soccorrere le persone, prestare loro le prime cure prima di essere condotte al Centro e al Poliambulatorio che dipende dall’ASL di Palermo. Un lavoro condiviso soltanto con due assistenti. Non bisogna immaginare uno stuolo di operatori, nessun ospedale o dei posti letto… non c’è nulla, solo un Poliambulatorio normale, dove i Lampedusani si recano per consultare il loro medico. La storia è iniziata trent’anni fa quando quattro tunisini sono arrivati su una barchetta, man mano sono aumentati a 350.000, un numero che cresce di continuo.

Il primo sopralluogo del film per scrivere la sceneggiatura tratta dai libri di Bartolo risale al 2017. Lui in questi anni ha scritto Lacrime di sale e Le stelle di Lampedusa, nel film abbiamo fatto un pot-pourri tra l’uno e l’altro per evitare di tralasciare cose importanti. In quell’occasione Pietro mi ha fatto conoscere non solo i suoi familiari ma anche i suoi amici e i Lampedusani, CONDIVIDENDO CON ME IL CLIMA AFFETTIVO CHE E’ RIUSCITO A CREARE ATTRAVERSO IL SUO SPESSORE UMANO E LA SUA PROFESSIONE.

Le ultime dichiarazioni dell’attuale sindaco dell’isola e la lettera aperta che ha scritto il presidente del Consiglio hanno fatto virare il fenomeno di Lampedusa dall’umanitario al politico. Nour diversamente è un film che definirei ‘umanista’, ho scelto di raccontare una storia reale, credibile, autentica fino all’ultimo dettaglio.

Immagino che nella tua formazione ci siano tracce importanti del grande maestro Ermanno Olmi: ogni film rispecchia nella sua essenza la dignità di una storia. Quanto nella tua cifra stilistica resta di quell’insegnamento?

Un rapporto professionale che è durato quaranta anni, lungi da me però fare un film alla Olmi. Lui nei suoi ultimi lavori era arrivato all’essenza dell’essenza, ogni scena era un tableau vivant, nel film Il mestiere delle armi ogni singola scena diventa un tableau vivant. Gli interessava raccontare la realtà in un’inquadratura, non gli importava del montaggio. Mi dispiace molto che Nour è l’unico film di quelli che ho girato che Olmi non ha potuto vedere.

Per me lo sguardo del regista rispetto alla ricerca dell’autenticità nel reale è fondamentale. Questo potrebbe essere l’insegnamento che Olmi mi ha lasciato in eredità. Se pensi di fare un film a Lampedusa importando un cast improbabile parti con il piede sbagliato. Sono andato sull’isola soltanto con il protagonista e due suoi collaboratori, il resto è stato costruito con la gente del posto andando nei bar, nelle case, al porto. Le persone dell’isola che nel film interagiscono con la bambina non recitano, fanno la loro parte in funzione di una scena cinematografica che però coincide con la realtà che vivono.

Diffido molto quando nella macchina da presa si vede il teatrino dell’inquadratura, le persone vere, reali conferiscono più forza all’intelaiatura narrativa del film.

Infondo cos’è che dà più fastidio al potere oggi se non quando racconti la realtà in un certo modo? Poiché narrare la realtà presume la libertà di espressione se questa libertà manca è certo che non farai mai un bel film.

Evocare la realtà significa anche stimolare le emozioni.

Negli uffici di produzione si rifletteva insieme su chi potesse interpretare il ruolo di Bartolo. Consideravo due possibilità: la prima che Bartolo recitasse se stesso in modo pregevole come aveva già fatto in Fuocoammare, spostando l’asse sul piano documentaristico, senza alla fine perdere nulla sul piano drammaturgico. Per evitare di seguire le tracce del film di Francesco Rosi ho pensato fosse meglio farlo interpretare da un attore come Sergio Castellitto che evocasse la figura di Bartolo nei pensieri, nei modi, nella parlata. Adesso va molto di moda assomigliare il più possibile al personaggio che racconti mentre la nostra intenzione puntava a evocare la realtà non a riprodurla.

Sono due cose ben distinte che conducono su territori completamente separati l’uno dall’altro, non si può mescolare la rappresentazione con l’evocazione. Nel tuo dialogo con la macchina da presa, dovresti asciugare tutto ciò che di finto hai di fronte per riuscire a evocare la verità che percepisci, PER ENTRARE IN RISONANZA CON QUESTA VERITA’.

Cerco sempre di evitare tutti gli orpelli della macchina cinema e della recitazione. Mi piace mescolare le carte, saper distinguere ciò che finto da ciò che non lo è… ricercare l’autenticità totale. Ad esempio la scena dello scontro tra Ismaila Mbaye – nel ruolo dello scafista – e Castellitto, si dimostra vincente da questo punto di vista. Ismaila, un artista così sensibile al fenomeno migratorio ha raggiunto la realtà della messa in scena scavando all’interno di se stesso, confrontandosi con caratteristiche umane molto distanti dalla sua personalità. Dovendo per forza immedesimarsi in quella parte non ha rinunciato a trasporre nella sua interpretazione la propria esperienza di vita.

Ismaila è stato all’altezza della sfida recitando il ruolo dello scafista, parte non facile per lui senegalese nato nell’isola di Gorée, punto di partenza della deportazione degli schiavi verso le Americhe. Nello scontro con Castellitto si sente una forte energia in entrambi.

A proposito della bambina, Nour racconta una storia vera…

Il 3 ottobre del 2013 una grande tragedia avveniva di fronte a Lampedusa, il naufragio di una barca che portava prevalentemente eritrei e somali. Ci siamo ispirati a quella storia. Una bambina nigeriana sopravvissuta alla disgrazia aveva perso i suoi genitori. Anche la storia di due fratelli siriani ci aveva colpito, alla fine per rendere giustizia a tutti abbiamo pensato di fare un racconto unico cambiando identità alla bambina che nel film è diventata di origini siriane. Il filo drammaturgico che abbiamo seguito racchiudeva queste perdite. Bartolo usa una bella frase quando parla dell’isola: per gli altri, Lampedusa è uno scoglio in mezzo al mare, per me invece è un salvagente in mezzo al mare.

Nel film volutamente non ci sono date, didascalie, riferimenti concreti, proprio per rispettare la scelta di evocare la realtà piuttosto che rappresentarla. Abbiamo preferito ricostruire la situazione dell’hangar che contiene i corpi di quella tragedia del 2013 come ci è stata raccontata da Bartolo piuttosto che inserire riprese televisive dell’epoca.

Un modo di mettere in scena che consente di rimanere in una dimensione atemporale e universale.

Esattamente, se inizi a inserire didascalie, dati, localizzazioni, tutto questo condiziona la forma della narrazione. Tutti i giorni la gente in televisione vede la cronaca delle migrazioni attraverso le inquadrature girate sull’isola di Lampedusa. Non si può proporre al pubblico ciò che già vede in televisione tutte le sere. In Nour ci siamo astratti dalla realtà descritta ogni giorno nelle news.

Se racconti una storia del genere, devi essere cosciente che la vuoi far arrivare al cuore del pubblico.

Ricordo una domanda che avevo posto a Ronconi durante un mio documentario sul teatro Piccolo di Milano: cosa si aspettava dal pubblico quando metteva in scena un’opera, come si aspettava che gli spettatori reagissero. Una domanda in fondo banale ma la risposta di Ronconi era stata fulminea: “A me interessa semplicemente che la gente che entra al Piccolo teatro quando esce dopo aver visto la rappresentazione sia diversa da come è entrata”. Si tratta dunque di attivare delle trasformazioni, di percepire dopo la visione di un film un cambiamento NEL PROPRIO SENTIRE E NELLA PROPRIA VISIONE DEL MONDO.

In Nour sei riuscito a narrare attraverso il personaggio di Bartolo la predisposizione dell’animo umano nel mantenersi vigili e in attesa, pronti ad accogliere, a prendersi cura di chi ha bisogno, ad aiutare l’altro con discernimento e coraggio.

Paradossalmente ciò che mi interessava di più di Lampedusa non era l’isola che peraltro fuori stagione diventa simile ad Alcatraz, una specie di caserma a cielo aperto. Sei accerchiato la mattina al bar prendendo il caffè da carabinieri, guardia costiera e di finanza, esercito, paracadutisti… a me interessava raccontare un’altra storia, quella del Poliambulatorio: il “fortino” costruito da Bartolo per difendere queste persone, per curarle e offrire loro una possibilità di sopravvivenza. Un fortino sotto assedio. Il film tranne alcuni fotogrammi di paesaggi epici che ritraggono l’isola si svolge tutto volutamente nell’ambulatorio. La bambina siriana Nour viene portata all’ambulatorio, cerca ripetutamente di scappare perché nella sua ricerca della madre nemmeno si rende conto di essere arrivata su un isola circondata dal mare. Questo particolare deriva da un racconto che mi aveva fatto un vecchietto lampedusano, un pescatore al quale due tunisini avevano chiesto dove si trovasse la stazione dei treni.

Mi fai sorridere e venire in mente una mia giovane paziente nigeriana che seguo nell’associazione DUN, una onlus dedicata alle cure psicologiche gratuite ai migranti, lei quando è arrivata in Libia pensava di essere arrivata in Italia. A proposito della fine del film e della ricerca della madre di Nour si può accennare qualcosa?

Direi con un sorriso di vedere direttamente il film…

——

NOUR – Waiting and in solitude

Dialogue with Maurizio Zaccaro

Edited by Barbara Massimilla – August 27, 2020

In the film Nour, the separation between a mother and a daughter, their losing sight of each other during the migratory journey, is a tragedy within a tragedy, the one that has been afflicting people forced to flee from wars, poverty, famine, to leave their places of origin in search of a better life for thirty years. I would like to begin with a quote dear to you from a Persian mystic, a phrase from Sa’di of Shiraz about the sensitivity that every man should develop by predisposing himself inwardly to perceive the pains, the sufferings of the other.

It is a phrase of his from the 1200s and expresses a very particular worldview: “All the sons of Adam form one body, they are of the same essence. When time afflicts one part of the body with pain, the other parts also suffer. If you do not feel the pain of others, you do not deserve to be called a man. If you do not feel each other’s pains in the end you cannot even be called a man.“

I was thinking from a psychoanalytic point of view of the process of identification that is activated in interpenetrating oneself in listening to the other, entering from within a deep relationship into the life and world of the other, from this point of view also making one’s own what are his wounds and pains in order to transform them.

It is no coincidence that this phrase is engraved in several languages on the entrance wall of the United Nations building in New York. Sa’di of Shiraz was a Sufi, it would belong to the past, and yet with the passage of centuries it would seem that humanity has stood still on this issue, that it has yet to reflect on the essence of this message, on the issues related to it.

There is much talk without incisive action; the contemporary world suffers from a lack of true, balanced, decisive actions that reflect a deep elaboration on the human condition and its destiny. With Pietro Bartolo, a doctor from Lampedusa, you have described a symbolic figure in some ways archetypal. Bartolo so masterfully played by Castellitto has the flavor of ethical and ancient characters, he proposes a model of existence that must be defended because, after all, in our days it is the only one that gives authentic meaning to life, to living together.

Pietro Bartolo is a doctor who fully did his job in Lampedusa, before becoming a member of the European Parliament two years ago. He never wanted to be a hero, even though he rescued and treated 350,000 human beings, he has always maintained that he simply did his duty as a doctor. He expresses himself in blunt, direct words. One senses his having felt lonely, in fact there was always a total vacuum around him FROM THE INSTITUTIONS. He pursued his professional and human endeavors in solitude. Alone on a pier he welcomed a multitude of loneliness.

Lampedusa’s pier in the past was made of stone with no shelter from the sun, now it is a long strip of asphalt stretched out into the sea on which Bartolo has had gazebos built to rescue people, give them first aid before being taken to the Center and the Outpatient Clinic that depends on the ASL of Palermo. A job shared with only two caregivers. You don’t have to imagine a throng of caregivers, no hospital or beds-there is nothing, just a normal Outpatient Clinic where Lampedusians go to consult their doctor. The story began 30 years ago when four Tunisians arrived on a small boat, gradually growing to 350,000, a number that keeps growing.

The first survey of the film to write the screenplay from Bartolo’s books was in 2017. He in recent years wrote Tears of Salt and The Stars of Lampedusa, in the film we made a pot-pourri between one and the other to avoid leaving out important things. On that occasion, Pietro introduced me not only to his family members but also to his friends and Lampedusans, SHARING WITH ME THE AFFECTIVE CLIMATE THAT HE WAS ABLE TO CREATE THROUGH HIS HUMAN SPACE AND PROFESSION.

The latest statements by the island’s current mayor and the open letter that the prime minister wrote have turned the Lampedusa phenomenon from the humanitarian to the political. Nour differently is a film I would call ‘humanist,’ I chose to tell a real, credible, authentic story down to the last detail.

I imagine that in your training there are important traces of the great master Ermanno Olmi: each film reflects in its essence the dignity of a story. How much in your stylistic figure remains of that teaching?

A professional relationship that lasted forty years, far be it from me, however, to make an Olmi film. He in his later works had gotten to the essence of the essence, every scene was a tableau vivant, in the film Il mestiere delle armi every single scene becomes a tableau vivant. He was interested in telling the reality in a frame, he didn’t care about editing. I am very sorry that Nour is the only film of those I made that Olmi could not see.

For me, the director’s gaze with respect to the search for authenticity in the real is fundamental. This could be the lesson that Olmi bequeathed to me. If you think of making a film in Lampedusa by importing an unlikely cast you are starting off on the wrong foot. I only went to the island with the main character and two of his collaborators, the rest was built with the locals by going to bars, houses, the port. The people on the island who interact with the little girl in the film are not acting, they play their part according to a cinematic scene that, however, coincides with the reality they live.

I am very wary when the camera shows theatrical framing, real, real people give more strength to the narrative framework of the film.

After all, what bothers power more today than when you narrate reality in a certain way? Since telling reality presumes freedom of expression if this freedom is lacking it is certain that you will never make a good film.

Evoking reality also means stimulating emotions.

In the production offices, we were pondering together who could play the role of Bartolo. I considered two possibilities: the first was for Bartolo to play himself admirably as he had already done in Fuocoammare, shifting the axis on the documentary level, without ultimately losing anything on the dramaturgical level. To avoid following in the footsteps of Francesco Rosi’s film, I thought it best to have him played by an actor like Sergio Castellitto who would evoke the figure of Bartolo in his thoughts, mannerisms, and speech. Now it is very fashionable to resemble as much as possible the character you tell while our intention aimed at evoking reality not reproducing it.

They are two very distinct things that lead into completely separate territories from each other, you cannot mix representation with evocation. In your dialogue with the camera, you should dry up everything fake in front of you in order to be able to evoke the truth you perceive, TO COME IN RESONANCE WITH THIS TRUTH.

I always try to avoid all the trappings of the film machine and acting. I like to mix it up, to be able to distinguish what is fake from what is not … to seek total authenticity. For example, the scene of the confrontation between Ismaila Mbaye – in the role of the scafista – and Castellitto, proves successful in this respect. Ismaila, an artist so sensitive to the phenomenon of migration has achieved the reality of staging by digging inside himself, confronting human characteristics that are very distant from his personality. Having to necessarily identify with the part, he did not refrain from transposing his own life experience into his performance.

Ismaila rose to the challenge by playing the role of the scafista, not an easy part for him a Senegalese born on the island of Gorée, the starting point of the deportation of slaves to the Americas. In his clash with Castellitto, one can feel a strong energy in both of them.

Speaking of the little girl, Nour tells a true story….

On October 3, 2013, a great tragedy occurred in front of Lampedusa, the sinking of a boat carrying mostly Eritreans and Somalis. We were inspired by that story. A little Nigerian girl who survived the misfortune had lost her parents. The story of two Syrian brothers had also struck us, and in the end to do justice to all we thought of making a unique story by changing the identity of the little girl who became of Syrian descent in the film. The dramaturgical thread we followed encapsulated these losses. Bartolo uses a beautiful phrase when talking about the island: for others, Lampedusa is a rock in the middle of the sea, but for me it is a life preserver in the middle of the sea.

In the film there are deliberately no dates, captions, concrete references, precisely to respect the choice to evoke reality rather than represent it. We preferred to reconstruct the situation in the hangar containing the bodies of that 2013 tragedy as told to us by Bartolo rather than inserting television footage from the time.

A way of staging that allows you to remain in a timeless and universal dimension.

Exactly, if you start inserting captions, data, localizations, all this conditions the form of the narrative. Every day people on television see the chronicle of migration through shots taken on the island of Lampedusa. You cannot propose to the audience what they already see on television every night. In Nour we abstracted ourselves from the reality described every day in the news.

If you tell a story like that, you have to be aware that you want to get it to the heart of the audience.

I remember a question I had asked Ronconi during one of my documentaries on the Piccolo theater in Milan: what did he expect from the audience when he staged an opera, how did he expect the audience to react. A basically banal question, but Ronconi’s answer had been lightning-fast: “I am simply interested in the fact that the people who enter the Piccolo teatro when they leave after seeing the play are different from how they entered.” So it is about activating transformations, about perceiving after watching a film a change IN YOUR OWN FEELING AND IN YOUR OWN VISION OF THE WORLD.

In Nour you managed to narrate through the character of Bartolo the predisposition of the human soul in keeping alert and expectant, ready to welcome, to care for those in need, to help the other with discernment and courage.

Paradoxically, what interested me most about Lampedusa was not the island, which moreover out of season becomes similar to Alcatraz, a kind of open-air barracks. You are surrounded in the morning at the bar having coffee by carabinieri, coast and finance guards, army, paratroopers… I was interested in telling another story, that of the Polyclinic: the “fort” built by Bartolo to defend these people, to care for them and offer them a chance to survive. A blockhouse under siege. The film except for a few frames of epic landscapes depicting the island all deliberately takes place in the outpatient clinic. The Syrian child Nour is brought to the clinic, repeatedly trying to escape because in her search for her mother she does not even realize that she has arrived on an island surrounded by sea. This detail comes from a story an old man from Lampedusa had told me, a fisherman who was asked by two Tunisians where the train station was.

You make me smile and bring to mind a young Nigerian patient of mine whom I follow in the DUN association, a non-profit organization dedicated to free psychological care for migrants, she when she arrived in Libya thought she had arrived in Italy. About the end of the film and the search for Nour’s mother can you mention anything?

I would say with a smile to see the film directly….

_____________________________________________

“En regardant le cinéma de Zaccaro, il est impossible de ne pas penser aux troupeaux de chevaux qui courent librement à travers les étendues illimitées, les mustangs. Le mot anglais mustang vient de l’espagnol mesteno qui signifie pas apprivoisé. Si je devais définir le réalisateur Maurizio Zaccaro avec un seul mot, j’utiliserais celui-ci: un réalisateur jamais apprivoisé, jamais homologué à la mode, jamais enclin au pouvoir. Les narrateurs comme celui-ci sont également rares parce qu’ils sont arrêtés, bloqués sans voix, en un mot évincés des jeux par ceux qui détiennent ce pouvoir. Eh bien, pour une fois, ne le faites pas. Laisse Zaccaro courir, laisse-le te dire ce qu’il veut, mais surtout ne lui mets pas de bride. “Nour” est un film extraordinairement beau pour ça. Parce que c’est simple, direct mais surtout si sauvage qu’il touche le cœur de tout le monde.”

Valerie Dubois – Montpellier

“Watching Zaccaro’s films, it’s impossible not to think of the herds of horses that run free across the limitless expanses, the mustangs. The English word mustang comes from the Spanish mesteno, meaning untamed. If I had to define director Maurizio Zaccaro with a single word, I’d use this one: a director never tamed, never approved of fashion, never inclined to power. Narrators like this are also rare because they are stopped, blocked without a voice, in a word ousted from the games by those who hold that power. Well, for once, don’t. Let Zaccaro run, let him tell you what he wants, but above all, don’t put a bridle on him. “Nour” is an extraordinarily beautiful film for that. Because it’s simple, direct but above all so wild that it touches everyone’s heart.”

Nour – Regia di Maurizio Zaccaro

C’è da sempre, nei film di Zaccaro, una tensione irrisolta tra finzione e documentario che, forse troppo semplicisticamente, si fa discendere dal rapporto fondamentale con Ermanno Olmi (a cui Nour è dedicato). Ed è vero che la lezione di quest’ultimo oggi si può intravedere, debitamente rimodulata, in certa fiction (frequentata con dignità dal medesimo Zaccaro, come nel tv movie Il sindaco pescatore, già con Sergio Castellitto). Non c’è da vergognarsene, perché la semplicità diretta della messa in scena e il prendere di petto personaggi, luoghi e situazioni possono essere valori preziosi che consentono di vedere e capire meglio. Come, appunto, accade in Nour, con la vicenda dolente della ragazzina in fuga dalla Siria e finita migrante senza famiglia a Lampedusa, ospite refrattaria del centro di accoglienza, tra gli sguardi diffidenti della popolazione locale e la rabbia smarrita dei suoi compagni. Zaccaro fa come Pietro Bartolo (Castellitto), medico stanco e segnato eppure mai domo nella sua missione umanitaria «nell’ultimo lembo d’Italia», autore del libro Lacrime di sale cui il film s’ispira, che si sottrae a ogni retorica e a ogni sentimentalismo. Sceglie quindi di far parlare le immagini, che siano una distesa di sacchi di plastica pieni di cadaveri o un piccolo cimitero dalle lapidi senza nome. Mostra, prima di raccontare, e qui riemerge la sua vocazione al documentario (come quando inquadra in sequenza i volti dei migranti che si presentano alla mdp). Fa cinema d’impegno civile in modo civile, e, per essere alla portata di tutti, non teme di farsi un po’ fiction. Una lezione preziosa, comunque la si pensi.

di Rocco Moccagatta per FILM-TV

There has always been, in Zaccaro’s films, an unresolved tension between fiction and documentary that, perhaps too simplistically, is descended from the fundamental relationship with Ermanno Olmi (to whom Nour is dedicated). And it is true that the latter’s lesson can be glimpsed today, duly remodeled, in certain fiction (attended with dignity by Zaccaro himself, as in the TV movie Il sindaco pescatore, formerly with Sergio Castellitto). There is no shame in this, because the straightforward simplicity of mise-en-scene and taking characters, places and situations head-on can be precious values that allow us to see and understand better. As, precisely, happens in Nour, with the sorrowful story of the young girl fleeing Syria and ending up a migrant without a family in Lampedusa, a refractory guest at the reception center, amidst the distrustful stares of the local population and the bewildered anger of her companions. Zaccaro does as Pietro Bartolo (Castellitto), a weary and scarred doctor yet never tame in his humanitarian mission “in the last strip of Italy,” author of the book Tears of Salt from which the film is inspired, who eschews all rhetoric and sentimentality. It therefore chooses to let the images speak, whether they are an expanse of plastic bags full of corpses or a small cemetery with nameless tombstones.It shows, before it tells, and this is where its vocation for documentary filmmaking resurfaces (as when it frames in sequence the faces of the migrants who present themselves to the mdp). He makes cinema of civil commitment in a civilized way, and, in order to be within everyone’s reach, he is not afraid to make himself a bit of fiction. A valuable lesson, however you think about it.

Au nom de toute l’équipe du film NOUR nous tenions vraiment à remercier le public de Bastia. Jeudi soir pour la projection officiel la salle était pleine, nous avons eu de retours magnifiques et très encourageants; cela nous touche beaucoup.

_____________________________________________

| NOUR. UN RITRATTO SEMPLICE DI UNA REALTÀ COMPLESSA, E DI UNA TRAGEDIA CHE ATTENDE ANCORA UNA SOLUZIONE. NOUR. A SIMPLE PORTRAIT OF A COMPLEX REALITY, AND A TRAGEDY THAT STILL AWAITS A SOLUTION. |

Fonte: MyMovies – Recensione di Emanuele Sacchi

martedì 26 novembre 2019

A Lampedusa sbarcano migranti. Quelli che riescono a toccare la terraferma, quantomeno. Molti invece muoiono annegati, o per ipotermia. Altri ancora arrivano lì, ma sono stati separati dalla rispettiva famiglia: come Nour, una ragazzina siriana costretta dalla guerra a lasciare la propria patria, rimasta senza la madre Fatima. Pietro Bartolo, il dottore che si occupa di soccorrere i migranti, prende a cuore il caso di Nour.

Lampedusa, terra di confine. Luogo della speranza e della sua frustrazione: l'”isola del sale” è stato teatro negli ultimi anni di sbarchi di moltitudini di esseri umani, quasi mai trattati come tali e disposti a tutto per la possibilità di un futuro migliore.

Nour di Maurizio Zaccaro, nella sua semplicità di linguaggio e umiltà di atteggiamento, può vantare diversi meriti. In primis quello di affrontare la vicenda attraverso un caso esemplare, senza presentare verità assolute o facili manicheismi. Anche il personaggio più vicino a incarnare la figura di villain, lo scafista senegalese Sandy, ha modo di esporre il suo punto di vista, attraverso un confronto deciso con Bartolo; e così per una giornalista, che ha la possibilità di smentire il pregiudizio del dottore con i fatti, dimostrando un’umanità che va al di là del sensazionalismo da ricerca dello scoop a tutti i costi.

Zaccaro ritorna a lavorare con Sergio Castellitto, dopo il film tv Il sindaco pescatore, e ritorna sul tema dell’immigrazione dopo L’articolo 2. Nour trae spunto da una vicenda realmente accaduta e raccontata in “Lacrime di sale”, scritto dallo stesso Bartolo insieme a Lidia Tilotta a coronamento di un infaticabile lavoro di soccorso e assistenza, fisico e spirituale, svolto dal medico a Lampedusa.

Il suo cinema apparentemente prosaico si rivela nuovamente vincente in Nour, dove la polifonia di personaggi e relativi pareri prova a ricostruire le mille sfaccettature di un dramma in cui è più semplice additare presunti colpevoli che trovare delle soluzioni concrete. I confronti di Bartolo con padre Giovanni o con altri “scettici” rappresentano altrettante occasioni per ridiscutere il nostro ruolo di occidentali privilegiati di fronte a una situazione apparentemente senza via di uscita, e che riguarda tutti noi. Come in una breve scena ambientata in un bar di Lampedusa, quando finalmente Bartolo trova il modo di sedersi e dimenticare, per un attimo, l’affanno continuo tra le corsie dell’ospedale. È qui che un fotoreporter confessa al medico di “votare a destra”, perché terrorizzato da quel che avviene in città come Ferrara, in cui la mafia nigeriana si è impossessata di un intero quartiere. E Bartolo, anziché presentare facili risposte, ascolta, capisce, solo in parte smentisce.

Anche questo apparentemente “indifendibile” punto di vista, secondo la vulgata corrente, ha luogo di esistere nella concezione orizzontale e attenta alle contraddizioni di Zaccaro. Per questo sarebbe semplicistico e miope accanirsi contro i limiti di messa in scena o di budget di Nour, così come attaccarlo per una “televisività” da fiction di prima serata. Il linguaggio del regista, dimesso e vicino alla quotidianità del piccolo schermo, è volutamente privo di ogni orpello autoriale, di qualunque possibilità di strumentalizzare la tragedia per metterla al servizio di un mero esercizio di stile. Zaccaro segue la lezione di Ermanno Olmi, a cui Nour è dedicato: un cinema etico parte innanzitutto dall’umiltà, dal fatto di non voler piegare la realtà o, peggio, la tragedia umana al proprio volere di autore

Lampedusa is landing migrants. Those who manage to touch land, at least. Many instead die by drowning, or by hypothermia. Still others arrive there but have been separated from their respective families: like Nour, a little Syrian girl forced by war to leave her homeland, left without her mother Fatima. Pietro Bartolo, the doctor in charge of rescuing migrants, takes Nour’s case to heart.

Lampedusa, borderland. Place of hope and its frustration: the “island of salt” has been the scene in recent years of landings of multitudes of human beings, almost never treated as such and willing to do anything for the chance of a better future.

Maurizio Zaccaro’s Nour, in its simplicity of language and humility of attitude, can boast several merits. First and foremost, that of approaching the story through an exemplary case, without presenting absolute truths or easy Manichaeism. Even the character closest to embodying the figure of the villain, the Senegalese boatman Sandy, has a way of exposing his point of view, through a decisive confrontation with Bartolo; and so for a journalist, who has a chance to refute the doctor’s prejudice with facts, demonstrating a humanity that goes beyond scoop-seeking sensationalism at all costs.

Zaccaro returns to work with Sergio Castellitto, after the TV film Il sindaco pescatore, and returns to the theme of immigration after L’articolo 2. Nour takes its cue from a real-life event recounted in Tears of Salt, written by Bartolo himself together with Lidia Tilotta as a culmination of the doctor’s tireless relief and assistance work, both physical and spiritual, in Lampedusa.

His seemingly prosaic cinema again proves successful in Nour, where the polyphony of characters and related opinions tries to reconstruct the myriad facets of a drama in which it is easier to point at alleged culprits than to find concrete solutions. Bartolo’s confrontations with Father John or other “skeptics” represent as many opportunities to re-discuss our role as privileged Westerners in the face of a seemingly dead-end situation that affects us all. As in a brief scene set in a bar in Lampedusa, when Bartolo finally finds a way to sit down and forget, for a moment, the constant wheezing between hospital wards. It is here that a photojournalist confesses to the doctor that he “votes right,” because he is terrified of what is happening in cities like Ferrara, where the Nigerian mafia has taken over an entire neighborhood. And Bartolo, instead of presenting easy answers, listens, understands, and only partially refutes.

Even this seemingly “indefensible” point of view, according to the current vernacular, has place in Zaccaro’s horizontal, contradiction-conscious conception. That is why it would be simplistic and short-sighted to rage against Nour’s staging or budget limitations, as well as to attack him for a prime-time drama “televisiveness.” The director’s language, dim and close to the everyday life of the small screen, is deliberately devoid of any authorial trappings, of any possibility of instrumentalizing tragedy to put it at the service of a mere exercise in style. Zaccaro follows the lesson of Ermanno Olmi, to whom Nour is dedicated: an ethical cinema starts first and foremost from humility, from not wanting to bend reality or, worse, human tragedy to one’s will as an auteur.

_____________________________________________

Cinema – Il fatto quotidiano – Davide Turrini

Nour, mettiamo da parte tutti i riferimenti a partiti e leader politici e guardiamo questo film

Nour, let’s put aside all references to political parties and leaders and watch this movie.

Il film di Maurizio Zaccaro presentato al 37esimo Torino Film Festival, è uno stralcio significativo della quotidianità recente di Pietro Bartolo, il medico che dal 1992 si occupa di soccorrere i migranti sull’isola di Lampedusa. Sergio Castellitto si immerge nel personaggio modello Actor’s

Facciamo tutti una piccola rinuncia. Mettiamo da parte tutti i riferimenti a partiti e leader politici, senza pensare nemmeno a cronaca e tweet, e guardiamo Nour. Il film di Maurizio Zaccaro presentato al 37esimo Torino Film Festival. Stralcio significativo della quotidianità recente di Pietro Bartolo, il medico che dal 1992 si occupa di soccorrere i migranti sull’isola di Lampedusa. Zaccaro, scuola Ermanno Olmi, non è un cineasta che vuole imporre lezioncine morali tra il rosso e il nero, anzi tra l’arancione e il grigio. Il maestro bergamasco ha sempre suggerito una prospettiva umanistica, uno sguardo oltre steccati e divisioni terreni, dritto nell’anima dell’uomo. E Nour rientra in pieno in questa “ipotesi di cinema”.