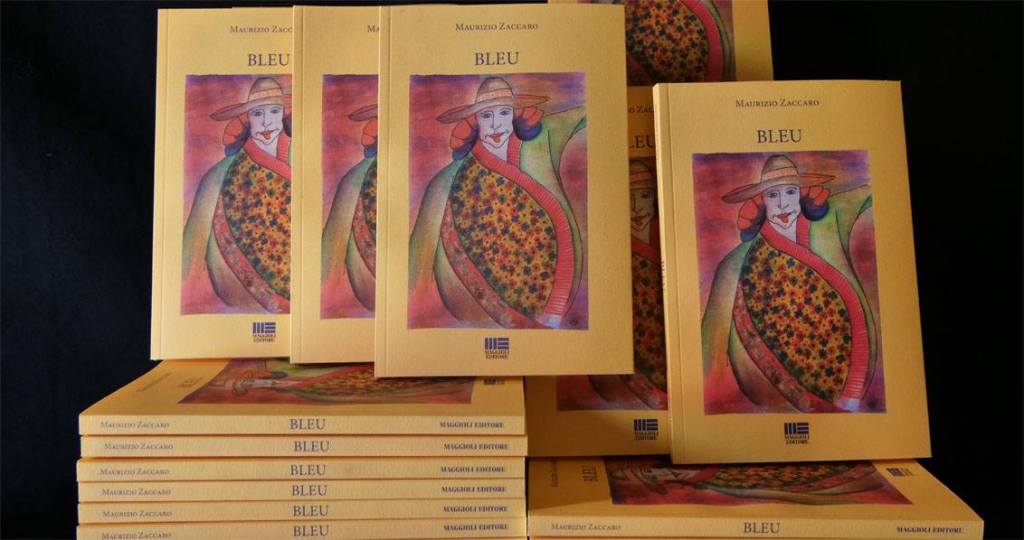

BLEU

Un breve romanzo diviso in due tempi “cinematografici” che scorrono paralleli. Due storie ovviamente destinate a intrecciarsi fra loro. Nella prima, un’anziana attrice di prosa affronta con originale determinazione le avvisaglie dell’Alzheimer. Nell’altra, una giovane donna sfida con coraggio la malattia della persona amata, fino alle estreme conseguenze. In questa biforcazione del destino che avvolge i protagonisti di entrambi i racconti non viene dato alcuno spazio alla mestizia ma solo al paradosso, a volte involontariamente comico, che determinate situazioni portano con sé. Ovvero, la capacità d’inventarsi di tutto pur di sconfiggere, anche a costo di dolorosi sacrifici, le avversità che la vita ci riserva e, con esse, le menzogne delle multinazionali del farmaco che detengono il monopolio delle cure sulla nostra salute. “L’ultima volta che sono andato dal dottore mi ha dato tante medicine che, una volta guarito, sono stato male per un mese intero”. La battuta è di Groucho Marx.

Il testo è stato già portato in scena in forma di monologo da Valeria D’obici (nell’ambito del Montefeltro film School Festival) e , più recentemente a Torino, da Anna Cuculo.

A short novel divided into two “cinematic” times that run parallel. Two stories obviously destined to intertwine with each other. In the first, an elderly prose actress confronts the warnings of Alzheimer’s with original determination. In the other, a young woman courageously defies her loved one’s illness to the extreme. In this bifurcation of fate that envelops the protagonists of both stories, no room is given to sadness but only to the sometimes unintentionally comic paradox that certain situations bring. That is, the ability to invent anything in order to defeat, even at the cost of painful sacrifices, the adversities that life has in store for us and, with them, the lies of the multinational drug companies that hold a monopoly on the treatment of our health. “The last time I went to the doctor, he gave me so much medicine that, once I was cured, I was sick for a whole month.” The line is from Groucho Marx.

The text has already been staged in monologue form by Valeria D’obici (as part of the Montefeltro film School Festival) and , most recently in Turin, by Anna Cuculo.

ANNA CUCULO IN “BLU”

Anna Cuculo Group

BLU

Monologo sul tema dell’Alzheimer

Interpretato da Anna Cuculo

Adattamento dal romanzo “BLEU” di Maurizio Zaccaro a cura di A.Cuculo

Regia di Federica Crisà

Musiche originali di Angelo Chionna

Voce fuori campo di Albino Marino

Scene e costumi: Monica Cafiero – Luci: Rebecca Agostinelli

Il blu è la realtà invisibile che diventa visibile

Yves Klein

Maurizio Zaccaro, regista e sceneggiatore cinematografico, ha pubblicato nel 2017 con Maggioli Editori un romanzo intitolato Bleu, due racconti che si intrecciano e portano il peso di un interrogativo: l’eutanasia. Con una scrittura toccante e sempre rispettosa del dono della vita, l’autore però non concede spazio alla mestizia, bensì al paradosso, a volte involontariamente comico, che

determinate situazioni portano con sé: ovvero, la capacità di inventarsi tutto pur di sconfiggere, anche a costo di dolorosi sacrifici, le avversità che la vita ci riserva e, con esse, le menzogne delle multinazionali del farmaco che detengono il monopolio delle cure sulla nostra salute.

Ci siamo appassionati a entrambi i racconti; per ora abbiamo affrontato il primo, la cui protagonista è Adriana, un’anziana attrice di prosa che affronta con originale determinazione le avvisaglie dell’Alzheimer ponendosi la prospettiva dell’eutanasia attiva.

“…Quando aveva valicato il confine fra l’essere sana o irrimediabilmente malata? Che cosa stava interpretando quando, con un irrefrenabile tremore alle gambe, si era accorta che dalle labbra non uscivano più le battute che era abituata a recitare da anni? Non se lo ricordava…. Subdola come un

serpente nell’ombra, la strega stava stirando la sua mente come un mattarello sulla pasta…”

Nell’adattamento abbiamo cercato di renderne i forti contenuti e quella sottile comicità derivante proprio dal paradosso che spesso si presenta in determinati momenti della vita.

(ANSA) – TORINO, 05 OTT – Affrontare l’arrivo dell’Alzheimer sulla propria pelle, con un tocco di leggerezza, al limite del paradosso, che diventa, involontariamente comico.

E quanto fa Adriana, un’anziana attrice con i primi sintomi della malattia, protagonista del monologo ‘Blu’, interpretato da Anna Cuculo, in scena al Teatro Gobetti l’11 ottobre.

L’incasso derivato dallo spettacolo, adattamento dall’omonimo romanzo ‘Blu’, di Maurizio Zaccaro, a cura della stessa Cuculo, sarà devoluto in parte all’Associazione Alzheimer Piemonte.

Il testo di Zaccaro, centrato sul tema dei limiti estremi dell’esistenza, fino alla morte stessa e all’eutanasia, ha una scrittura toccante e sempre rispettosa del dono della vita, ma senza concedere spazio alla mestizia, con un occhio rivolto ad una certa comicità dell’esistenza stessa e della malattia.

“Nell’adattamento – dice Cuculo – abbiamo cercato di renderne i forti contenuti e quella sottile comicità derivante dal paradosso che spesso si presenta in determinati momenti della vita”.

“Che cosa stava interpretando quando, con un irrefrenabile tremore alle gambe, si era accorta che dalle labbra non uscivano più le battute che era abituata a recitare da anni? – si legge nel testo – Non se lo ricordava…Subdola come un serpente nell’ombra, la strega stava stirando la sua mente come un mattarello sulla pasta…”. (ANSA).

Blue is the invisible reality that becomes visible

Yves Klein

Maurizio Zaccaro, film director and screenwriter, published in 2017 with Maggioli Editori a novel entitled Bleu, two intertwining short stories that carry the weight of one question: euthanasia. With touching writing that is always respectful of the gift of life, however, the author does not allow room for sadness, but rather for the sometimes unintentionally comic paradox that

certain situations bring with them: namely, the ability to invent everything in order to defeat, even at the cost of painful sacrifices, the adversities that life has in store for us and, with them, the lies of the multinational drug companies that hold a monopoly on the treatment of our health.

We were passionate about both stories; for now we have tackled the first one, whose protagonist is Adriana, an elderly prose actress who faces with original determination the warnings of Alzheimer’s by posing the prospect of active euthanasia.

“…When had she crossed the line between being healthy or hopelessly ill? What was she playing when, with an irrepressible tremor in her legs, she had noticed that the lines she had been accustomed to reciting for years were no longer coming from her lips? She did not remember…. Sneaky as a

snake in the shadows, the witch was stretching her mind like a rolling pin on dough…”

In adapting it, we have tried to render its strong content and that subtle comedy arising precisely from the paradox that often arises at certain times in life.

BLEU

ESTRATTO

Le avevano detto che non esisteva nessuna pozione magica per sconfiggere la strega, Adriana la chiamava così, però qualcosa che ne rallentava la devastante progressione c’era. Ben magra consolazione. Distruzione delle cellule, demenza degenerativa, Alzheimer insomma. Parole terribili, mitigate solo dai sorrisi ebeti di amici e colleghi che le suggerivano di fare un fascicolo di parole crociate al dì, perché così il cervello si mantiene “vigile” e le cellule non muoiono come tante formiche asfissiate dal Baygon. Sì, sì. Diceva a tutti Adriana. Le faccio, non vi preoccupate che le faccio. Ma poi si limitava a leggere le vignette che, oltretutto, nemmeno la facevano ridere. Un’unica cosa confortava Adriana, sola nella sua raffinata casa romana: il silenzio. Luminosa e spaziosa, con le ampie finestre che si affacciavano sul cielo quasi sempre azzurro, quella casa era da più di trent’anni il suo porto d’arrivo dopo le estenuanti tournée in giro per l’Italia, ma anche all’estero. Il silenzio e quella luce la rigeneravano, le davano la forza di andare avanti anche senza una famiglia, gli affetti, gli amori.

Quelle cose lì insomma, che fanno più sopportabile la vita, almeno così si dice. Non che non ne avesse avute di storie anzi, ma per un motivo o per l’altro evaporavano nel nulla tutte nello stesso modo. Meglio non andare oltre… Diceva lei al “cretinetti” di turno. Meglio non farsi del male. E a quelli non sembrava vero, la prendevano in parola e scomparivano con il vento sotto le suole. Ora, che di anni ne aveva settantacinque, non c’era più bisogno di dire e di fare niente. La bellezza non era svanita, era semplicemente stata lavorata dal tempo. Lo sguardo era man mano diventato più acquoso, la pelle si era raggrinzita adattando così volto e gesti ai ruoli “da vecchia” che ormai le offrivano. L’affascinante Ljuba Andreevna Ranevskaja felice solo nel suo Giardino dei Ciliegi, un testo che sapeva interpretare, come avevano scritto in tanti, meglio della Cortese, era ormai solo una sbiadita fotografia, incorniciata in peltro, immobile sopra una mensola della libreria. Quando aveva valicato il confine fra l’essere sana o irrimediabilmente malata? Cosa stava interpretando quando, accompagnato da un irrefrenabile tremore alle gambe, si era accorta che dalle labbra non uscivano più le battute che era abituata a recitare da anni? Non se lo ricordava. Si ricordava invece con orrore l’espressione preoccupata dell’impresario che, il giorno successivo, l’aveva convocata nel suo ufficio. Era stanca forse? Aveva bisogno di riposo? Si poteva valutare una “temporanea” sostituzione. Adriana, che si era imposta di minimizzare l’accaduto, non voleva farsene una ragione, forse nemmeno capiva cosa in realtà le stava proponendo l’impresario. Sta di fatto che era

stata sostituita da una collega più giovane e, come diceva lui senza tanti giri di parole, più adeguata al ruolo. Nell’appartamento di via Rodi era cominciato così il pellegrinaggio di colleghi e amici. Visite prima quotidiane, poi sempre più saltuarie. Ora non vedeva più nessuno da tempo. Da quanto? Non se lo ricordava. A volte sfogliava l’agenda, cercava qualche amica da invitare se non per cena almeno per un tè, ma alla fine si fermava al prefisso e interrompeva la telefonata. L’unica volta che era andata fino in fondo le aveva risposto il marito dell’amica che, con tono seccato, le aveva detto: Hai voglia di scherzare oggi, Adriana? Giovanna se n’è andata due anni fa, dai, su… E aveva riattaccato. Se n’era andata cosa voleva dire? Che era partita? Che era morta, forse? Non l’avrebbe mai saputo. Subdola come un serpente nell’ombra, la strega stava stirando la sua mente come certe donne, specialmente dalle sue parti, sanno fare con pasta e mattarello. La casa era sempre la stessa, le cose da fare sempre quelle eppure, a ben vedere, qualcosa di strano c’era anche lì. In un primo momento Adriana non ci aveva fatto caso ma poi si trovava come ipnotizzata davanti ai quadri appesi alle pareti. Li guardava per minuti interi, immobile davanti al suo nome stampato a grandi caratteri su locandine teatrali che, al momento, non le dicevano assolutamente nulla. E sotto il suo nome, come a ribadire che era molto più importante l’attrice dell’opera, solo il titolo: Il giardino dei ciliegi, L’anitra selvatica, La Betìa, Madre Coraggio e i suoi figli, e tanti altri: una vita sul palcoscenico. Ma quale vita? La sua? Era proprio lei? Adriana, Adriana che ti succede? Si diceva. Poi un’altra voce spodestava la prima e intimava: Ma chi mai li avrà appesi al muro? Buttali via, non sono roba tua, buttali… No, non darle retta, sei tu quella lì, proprio tu! Tornava ad ammansire la prima voce. Sprazzi di lucidità in conflitto con la strega. Il nero contro il bianco. Questo Adriana lo sapeva bene, ma doveva fare alla svelta. Doveva agire in prima persona e subito, prima che qualcuno, fra i pochi amici rimasti, si fosse sentito in obbligo di darle una mano appioppandole una badante. Non l’avrebbe sopportato. Non doveva finire così, piuttosto sarebbe stato più giusto morire, magari in una di quelle cliniche svizzere dove ti fanno bere un bicchierino di qualcosa e ciao. Almeno questo era un concetto ancora nitido, uno sbarramento a doppio, triplo filo spinato come quelli che si vedono nei film di guerra, dietro il quale attendere il nemico. E così un giorno di tarda estate, con il caldo ancora feroce, nell’immenso stridore delle cicale, Adriana decideva, in completa solitudine, che la misura era colma. Avrebbe pensato lei al suo futuro non qualcun altro, e sapeva benissimo come…

excerpt

She had been told that there was no magic potion to defeat the witch, Adriana called it, however, something to slow its devastating progression was there. Well meager consolation. Cell destruction, degenerative dementia, Alzheimer’s in short. Terrible words, mitigated only by the ebetic smiles of friends and colleagues who suggested she do a file of crossword puzzles a day, because that way the brain stays “alert” and the cells don’t die like so many ants asphyxiated by Baygon. Yes. Adriana told everyone. I do them, don’t worry I do them. But then she would just read the cartoons, which, moreover, did not even make her laugh. Only one thing comforted Adriana, alone in her refined Roman home: silence. Bright and spacious, with large windows overlooking the almost always blue sky, that house had been her port of arrival for more than thirty years after exhausting tours around Italy, but also abroad. The silence and that light regenerated her, gave her the strength to go on even without a family, affections, loves. Those things there in short, that make life more bearable, at least that’s what they say. Not that she hadn’t had affairs on the contrary, but for one reason or another they all evaporated into thin air in the same way. Better not to go any further–she would say to the “cretin” on duty. Better not to get hurt. And to those it didn’t seem true, they would take her at her word and disappear with the wind beneath their soles. Now, that she was seventy-five years old, there was no need to say or do anything anymore. The beauty had not vanished; it had simply been worked over by time. Her gaze had gradually become more watery, her skin had wrinkled, thus adapting her face and gestures to the “old woman” roles now offered her. The charming Ljuba Andreevna Ranevskaya, happy only in her Cherry Orchard, a text she could interpret, as so many had written, better than Cortese, was now only a faded photograph, framed in pewter, motionless above a bookshelf. When had she crossed the line between being healthy or hopelessly ill? What was she playing when, accompanied by an irrepressible tremor in her legs, she had noticed that the lines she had been accustomed to reciting for years were no longer coming from her lips? She did not remember. Instead, she remembered with horror the worried expression of the impresario who had summoned her to his office the next day. Was she tired perhaps? Did she need rest? A “temporary” replacement could be considered. Adriana, who had forced herself to downplay what had happened, did not want to get over it; perhaps she did not even understand what the impresario was actually proposing to her. The fact was that she had been replaced by a younger and, as he put it so bluntly, more appropriate colleague for the role. At the apartment on Via Rodi the pilgrimage of colleagues and friends had thus begun. Daily visits at first, then increasingly sporadic. Now he had not seen anyone for some time. How long? He could not remember. Sometimes she would flip through her diary, looking for a few friends to invite if not for dinner at least for tea, but eventually she would stop at the area code and cut the call short. The only time she had gone all the way she had been answered by the friend’s husband who, in an annoyed tone, had said to her, Do you feel like fooling around today, Adriana? Giovanna left two years ago, come on, come on… And she had hung up. If she was gone what did she mean? That she had left? That she was dead, maybe? She would never know. Sneaky as a snake in the shadows, the witch was stretching her mind as some women, especially in her neck of the woods, know how to do with dough and rolling pin.

The house was always the same, the things to be done always the same, and yet, upon closer inspection, something strange was there too. At first Adriana paid no attention to it but then she found herself as if hypnotized before the pictures hanging on the walls. She would stare at them for minutes on end, motionless before her name printed in large letters on theater posters that, at the moment, said absolutely nothing to her. And under her name, as if to reiterate that she was far more important the actress than the play, only the title: The Cherry Orchard, The Wild Duck, The Bethel, Mother Courage and Her Children, and so many others: a life on the stage. But which life? Her own? Was it really her? Adriana, Adriana what’s the matter with you? It was said. Then another voice ousted the first and intimated: But who on earth would have hung them on the wall? Throw them away, they’re not your stuff, throw them away… No, don’t listen to her, you’re the one there, just you! Back to tame the first voice. Flashes of lucidity in conflict with the witch. The black against the white. This Adriana knew well, but she had to act quickly. She had to act herself and right away, before someone among her few remaining friends felt compelled to lend her a hand by saddling her with a caregiver.

He was not going to take it. It was not supposed to end like this, rather it would have been more just to die, maybe in one of those Swiss clinics where they let you have a little drink of something and bye-bye. At least that was still a crisp concept, a double, triple barbed-wire barrage like those you see in war movies, behind which to wait for the enemy. And so one late summer day, with the heat still fierce, in the immense screech of cicadas, Adriana decided, in complete solitude, that the measure was full. She would take care of her future not someone else, and she knew very well how….

Categorie

mauriziozaccaro Mostra tutti

Regista e sceneggiatore italiano.

Italian film director and screenplayer.