SOTTO IL SOLE – RACCONTI DI UOMINI, ANIMALI E OMBRE

UNDER THE SUN – TALES OF MEN, ANIMALS AND SHADOWS

***

Da CINEFORUM

Critica e cultura cinematografica

FOCUS: SOTTO IL SOLE. RACCONTI DI UOMINI, ANIMALI E OMBRE DI MAURIZIO ZACCARO

Recensione di Massimo Lastrucci

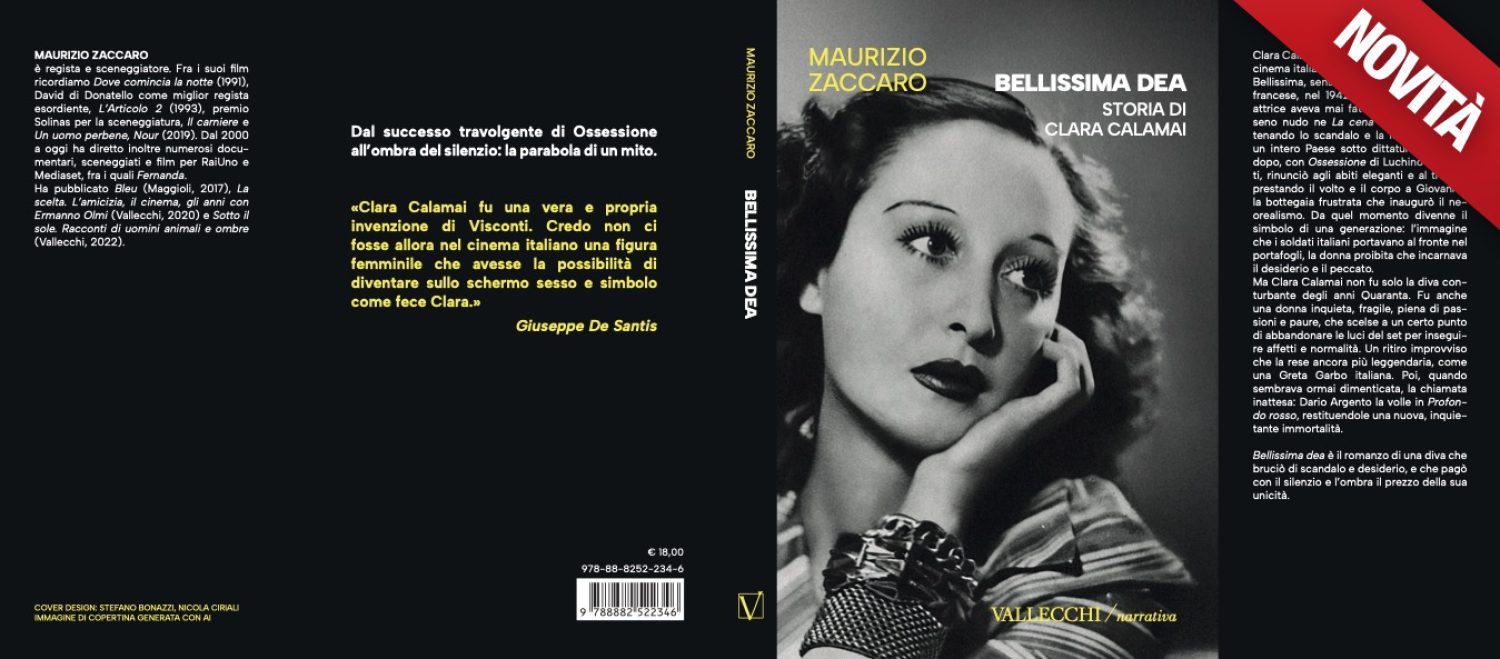

Maurizio Zaccaro è un navigato uomo di cinema (e di televisione, con gran successo) che ha sempre mostrato mano e inventiva sicura lavorando su storie realistiche e nella drammatizzazione di problematiche sociali. Il suo film più importante e conosciuto è Un uomo per bene (1999), partecipata ricostruzione del caso Tortora, anche se spicca nella sua filmografia un debutto, con sceneggiatura di Pupi Avati, Dove comincia la notte (1991), in cui mostra un certo penchant per atmosfere mistery, quasi fantastiche.

Nella sua seconda opera di narrativa, dopo Bleu (2017), questo suo lato “segreto” viene riportato alla luce, con bell’esito. Perché Sotto il sole (sottotitolo: Racconti di uomini, animali e ombre), edito da Vallecchi, è una esplorazione in dodici racconti sul tema del “dopo morte”, visto però dalla parte dell’anima e delle umane sensibilità, piuttosto che non le stereotipizzazioni orrorifiche del genere. Siamo nel ponte che porta dal mondo visibile al mondo invisibile e i trapassati (che non sempre ne sono coscienti, almeno all’inizio) trovano conforto nei loro affetti precedenti, conservando ricordi e natura, magari tentando contatti che si risolvono in un soffio di brezza, ora gelida ora tiepida.

Lo spavento qui non trova spazio e neppure il macabro o il crudele, se c’è vendetta (accade in La volpe rossa), sembra più un atto dovuto che non una maledizione. Ma non è solo una prerogativa umana la persistenza spirituale (in attesa, non si sa quando, di un ulteriore passaggio). Diafani (a parte qualche anima umana prava circondata da un’aura nerastra, simile a “quarzo nero”), e coerenti con il loro carattere in vita, cani, gatti, topi, volpi si aggirano, comunicando tra loro e soprattutto con gli umani.

Ora dolcemente dolenti, ora umoristici, quasi sempre con un piccolo twist finale a dar altre prospettive alla vicenda, i dodici racconti ci invitano così a non disperare, ad accettare l’ineluttabile. Perché, come scrive altrove Zaccaro, presentando il libro “C’è un soffio vitale nell’uomo che costituisce la sua parte immateriale ma anche il centro del pensiero, del sentimento, della volontà, della stessa coscienza morale. Si chiama anima e ogni anima, anche se non avrà più alcuna parte in tutto ciò che accade sotto il sole, è immortale”.

Questo abito morale e filosofico è il motore e il fine di queste novelle. La scrittura piana e scorrevole dell’autore evita le acrobazie linguistiche, le immagini truculente, ogni sospetto di spettacolarizzazione pulp, anche quando c’è in ballo una faida tra famiglie o ci si trova tra i loculi o nei laboratori degli obitori. C’è speranza sempre e pietas ovunque, persino quando si concede divertimenti particolari, ad esempio nella scelta dei nomi dei protagonisti.

Un po’ come accade spesso nei personaggi dei film di Marco Bellocchio, qui la gente comune, porta a volte nomi buffi (e insinuanti) anche se plausibili: Emilio Terrasanta (tecnico “truccatore” alle onoranze funebri, meglio dire: tanatoprattore in La dimensione dell’ombra); il colonnello Cesare Bonasorte (vedovo di L’ottavo piano che si ritrova con un appartamento un po’ affollato); Demetrio Lixi ( “pianista talentuoso anche se un po’ svagato” in Pour piano seul); l’obeso Giuliano Canal o la vicina di loculo Teresa Ognissanti (in Extra size) e così via, in una commedia umana che prosegue oltre la vita.

Maurizio Zaccaro is a seasoned film (and television, with great success) man who has always shown a sure hand and inventiveness in working on realistic stories and in dramatizing social issues. His most important and best-known film is Un uomo per bene (1999), a participatory reconstruction of the Tortora case, although a debut, with a screenplay by Pupi Avati, Dove comincia la notte (1991), in which he shows a certain penchant for mysterious, almost fantastic atmospheres, stands out in his filmography. In his second work of fiction, after Bleu (2017), this “secret” side of him is brought back to light, with beautiful results. Because Under the Sun (subtitle: Tales of Men, Animals and Shadows), published by Vallecchi, is an exploration in twelve short stories on the theme of the “after death,” seen, however, from the side of the soul and human sensibilities, rather than the stereotypical horror genre. We are in the bridge that leads from the visible world to the invisible world, and the departed (who are not always aware of this, at least at first) find solace in their former affections, preserving memories and nature, perhaps attempting contacts that result in a breath of breeze, now icy now warm.

Fright has no place here, nor does the macabre or cruel, if there is revenge (it happens in The Red Fox), seeming more like an act of duty than a curse. But spiritual persistence (waiting, we do not know when, for further passage) is not only a human prerogative. Diaphanous (apart from a few praying human souls surrounded by a blackish aura, similar to “black quartz”), and consistent with their character in life, dogs, cats, mice, foxes roam about, communicating with each other and especially with humans. Now gently sorrowful, now humorous, almost always with a little twist at the end to give other perspectives to the story, the twelve tales thus invite us not to despair, to accept the inescapable. Because, as Zaccaro writes elsewhere, introducing the book, “There is a vital breath in man that constitutes his immaterial part but also the center of thought, feeling, will, moral consciousness itself. It is called the soul, and every soul, although it will no longer have any part in everything that happens under the sun, is immortal.”

This moral and philosophical habit is the driving force and goal of these novellas. The author’s flat, flowing writing avoids linguistic acrobatics, truculent imagery, any suspicion of pulp showmanship, even when there is a family feud at stake or one finds oneself among the loculi or in morgue laboratories. There is hope always and pietas everywhere, even when indulging in peculiar amusements, for example in the choice of names for the protagonists. Somewhat as is often the case with characters in Marco Bellocchio’s films, ordinary people here sometimes bear funny (and insinuating) though plausible names: Emilio Terrasanta (“makeup” technician at the funeral home, better said: tanatoprattore in La dimensione dell’ombra); Colonel Cesare Bonasorte (a widower in L’ottavo piano who finds himself with a somewhat crowded apartment); Demetrio Lixi (“talented though somewhat scatterbrained pianist” in Pour piano seul); the obese Giuliano Canal or loculus neighbor Teresa Ognissanti (in Extra size) and so on, in a human comedy that continues beyond life.

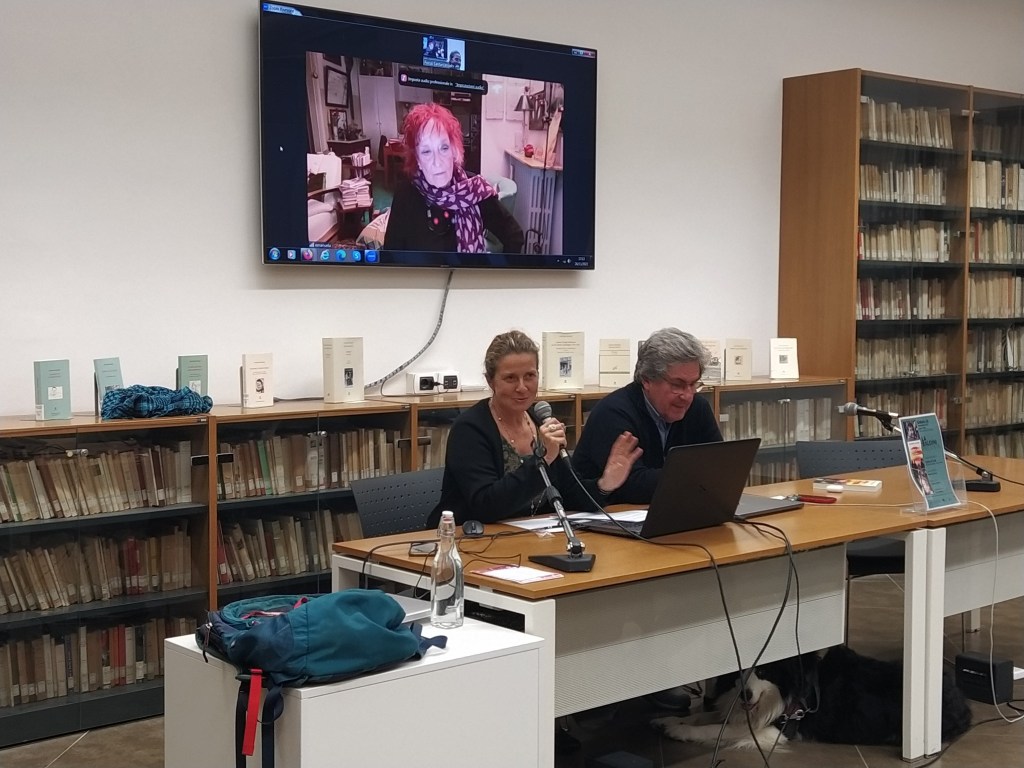

Prima presentazione di “SOTTO IL SOLE, RACCONTI DI UOMINI, ANIMALI E OMBRE” alla Biblioteca Baldini di Santarcangelo di Romagna. Grazie a tutti per essere venuti a trovarci. Prossimo appuntamento Mondadori Store di Piazza Duomo, Milano. Chi è interessato per altri incontri con l’autore può scrivere a info@vallecchi-firenze.it

First presentation of “UNDER THE SUN, STORIES OF MEN, ANIMALS AND SHADOWS” at the Baldini Library in Santarcangelo di Romagna. Thank you all for coming to see us. Next meeting Mondadori Store in Piazza Duomo, Milan. Those interested in other meetings with the author can write to info@vallecchi-firenze.it

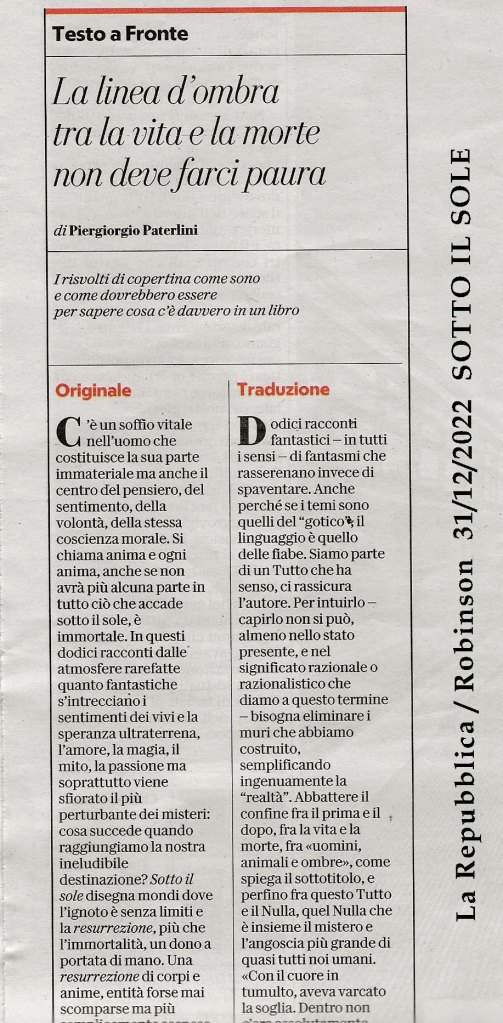

C’è un soffio vitale nell’uomo che costituisce la sua parte immateriale ma anche il centro del pensiero, del sentimento, della volontà, della stessa coscienza morale. Si chiama anima e ogni anima, anche se non avrà più alcuna parte in tutto ciò che accade sotto il sole, è immortale. In questi dodici racconti dalle atmosfere rarefatte quanto fantastiche si intrecciano i sentimenti dei vivi e la speranza ultraterrena, l’amore, la magia, il mito, la passione ma soprattutto viene sfiorato il più perturbante dei misteri: cosa succede quando raggiungiamo la nostra ineludibile destinazione?

Sotto il sole disegna mondi dove l’ignoto è senza limiti e la “resurrezione”, più che l’immortalità, un dono a portata di mano. Una “resurrezione” di corpi e anime, entità forse mai scomparse ma più semplicemente sospese in quel “varco temporale” dove vita e morte non hanno i confini così netti ai quali siamo stati grossolanamente educati. Del resto, come ha detto Vladimir Nabokov, se la vita è una grande sorpresa, non vedo perché la morte non potrebbe esserne una anche più grande.

There is a vital breath in man that constitutes his immaterial part but also the center of thought, feeling, will, and moral consciousness itself. It is called the soul, and every soul, although it will no longer have any part in everything that happens under the sun, is immortal. In these twelve stories with atmospheres as rarefied as they are fantastic, the feelings of the living and otherworldly hope, love, magic, myth, passion are intertwined, but above all, the most perturbing of mysteries is touched upon: what happens when we reach our inescapable destination?

Under the Sun draws worlds where the unknown is limitless and “resurrection,” rather than immortality, a gift at hand. A “resurrection” of bodies and souls, entities perhaps never disappeared but more simply suspended in that “temporal gateway” where life and death do not have the such sharp boundaries to which we have been grossly educated. After all, as Vladimir Nabokov said, if life is a great surprise, I see no reason why death could not be an even greater one.

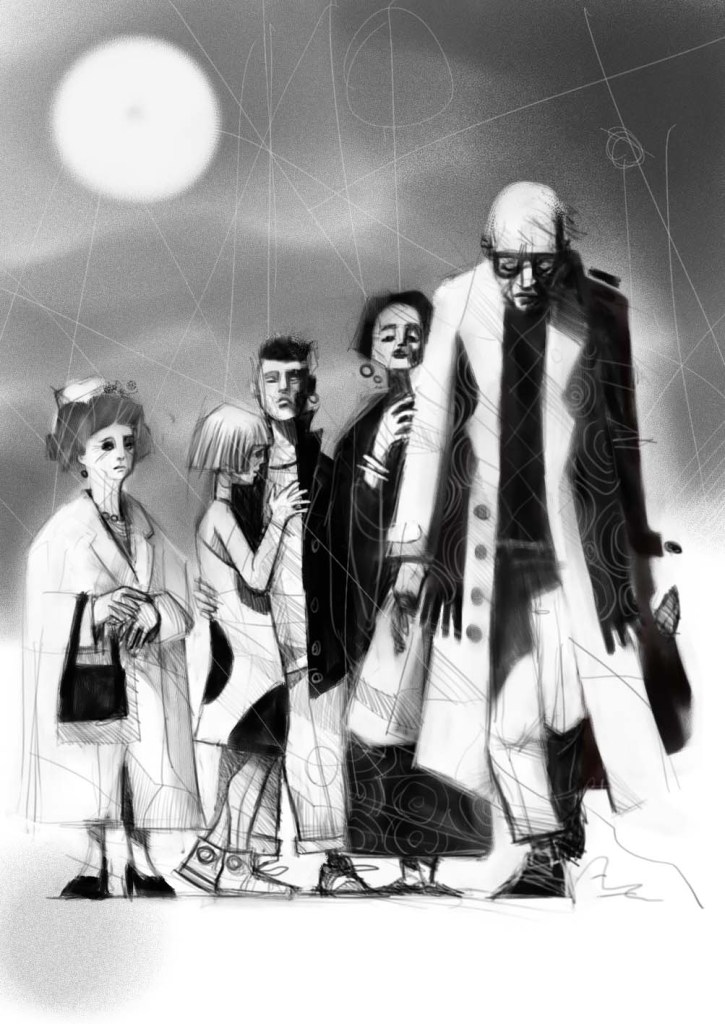

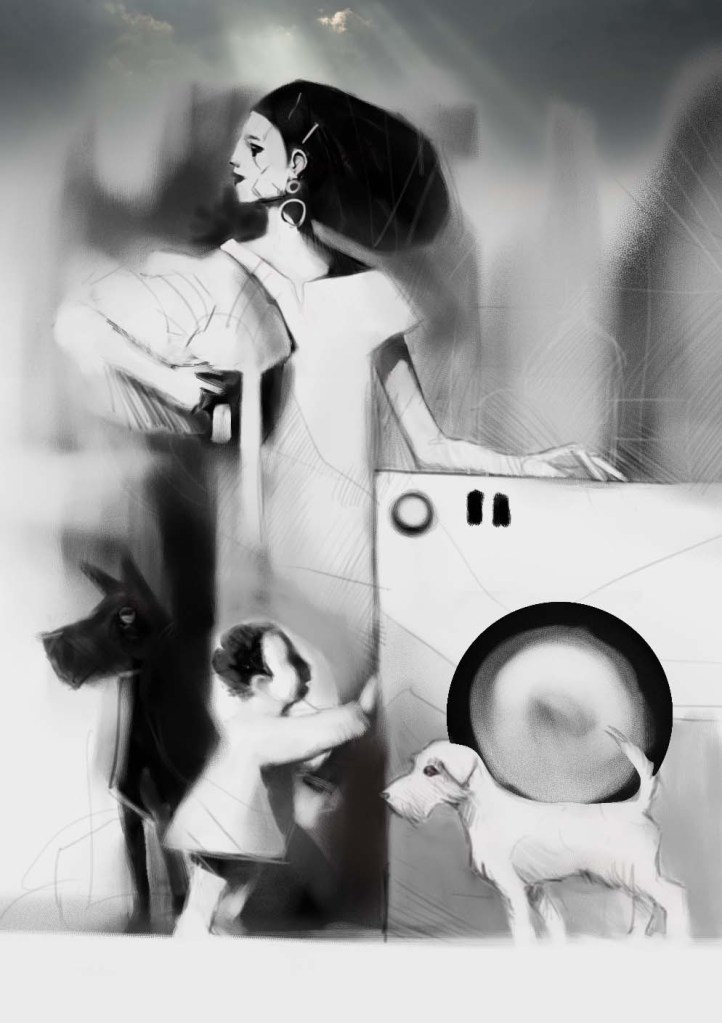

Copertina e illustrazioni di Roberto Ballestracci © 2022 Vallecchi Firenze

Prefazione

Emanuela Martini

Una signora in nero con una borsetta rosso fuoco e un’altra in giallo burro, come la regina d’Inghilterra, un colonnello vedovo in pensione, un pianista con una marsina troppo stretta e un po’ logora, una deejay che lavora in radio la notte, un parroco di campagna, e poi coppie che sono state insieme tutta la vita e fanno fatica a separarsi e mamme e bambini con gli occhi chiari come acqua, imprevedibili e visionari. E, insieme agli umani, tanti animali: una gatta bianca con gli occhi azzurri, una nera con un nastro rosa sulla testa, una vecchia labrador con la cataratta e un cucciolo giovane che si chiama Dan- te, un topolino beige e una volpe con una grande coda rossa: sono solo alcuni dei personaggi dei racconti di Sotto il sole – racconti di uomini, animali e ombre di Maurizio Zaccaro.

Indaffarati in attività che sono o, a volte, “paiono” normali, visibili a tutti o ad alcuni, fuori e dentro da condomini, supermercati, fattorie, trattorie, cimiteri, autobus, di giorno come di notte. Dove vanno? Da dove arrivano? Da quali interstizi del tempo e dello spazio emergono per tagliarci la strada, intrecciare le loro vite con le nostre, parlarci, guidarci? E, soprattutto, cosa ci fanno in casa nostra?

Ecco, le case (altre grandi protagoniste di queste storie). Luoghi classici della narrativa fantastica (tutta, anche cinematografica), che passano di mano in mano, da inquilino a inquilino, da proprietario a proprietario, conservando e tramandando ricordi e tracce, visibili o invisibili, degli occupanti precedenti. Case che non vo- gliamo, o non possiamo, lasciare: altrimenti dove vanno ad abitare la signora con la borsetta rossa, la gatta Lea, la labrador Marietta?

Ma, a differenza di quanto spesso accade, le case di Zaccaro, si tratti di appartamenti borghesi o case di campagna decadute, non sono malevole, ostili, pericolo- se ma, in qualche maniera, accoglienti, consolanti, “materne”. La nostra casa, le nostre cose, la nostra anima. Certo, nostra, ma anche di quelli che ci abitavano prima. Da queste secolari coabitazioni nascono gli intrecci tra di qua e di là, tra vivi e morti, più accentuati e stridenti, è ovvio, nel momento del trapasso, quando il nostro corpo sta da una parte e noi, staccati da lui, lo vediamo, e nel frattempo incontriamo nuovi amici e “coinquilini”, quelli che c’erano prima.

Ma andiamo con ordine. I racconti di Zaccaro iniziano, con una certa logica, in una casa funeraria, dove il mingherlino Emilio, un tanatoprattore (il professionista che si occupa delle cure igieniche ed estetiche dei cadaveri prima della cerimonia funebre), sta lavorando sul corpo del suo gemello eterozigote, il corpulento Aurelio, morto suicida. E qui, all’insaputa di Emilio, cominciano le avventure di Aurelio (e le nostre) nel regno delle ombre. Ombre letterali, quelle che ci portiamo attaccate addosso, che possono essere mutevoli e, a volte, dispettose, ma dalle quali, come insegna E.T.A. Hoffmann nel- la Notte di San Silvestro, è pericolosissimo separarsi. I Racconti di Hoffmann, bizzarre storie di anime e ombre vaganti, mercanti di occhi e seducenti automat che prendono vita, tutte ambientante in un inizio 800 quotidiano e concreto, sono certamente una fonte di ispirazione per l’autore, che non si allontana mai da un raggio visivo plausibile e consueto. Ma intorno aleggiano anche altri “padri”: Edgar Allan Poe, con le sue donne dai lunghi capelli corvini o fragilmente bionde, qualche suggestione rossettiano-preraffaellita, con morti per annegamento e acque che turbinano, tocchi di saggezza esopiana, la tenerezza del più triste dei favolisti classici, Hans Christian Andersen, che faceva transitare tra diversi mondi le sue creature, umane, animali, ibride. Anche un soldatino di stagno può avere un cuore e una vita. Figurarsi gli animali che qui, come in tutte le fiabe (per quanto nere) che si rispettino, hanno ruoli importantissimi. Non solo nel primo racconto, ma in molti altri, sono il tramite tra le varie dimensioni, quelli che percepiscono l’ignoto, che “vedono” quando noi sentiamo solo un refolo di aria fredda, che ci aspettano quando li raggiungiamo “di là” per aiutarci ad adattarci alla nuova condizione. Giocherelloni come i cani, chiacchierone come le gat- te, sono presenze indispensabili di quegli appartamenti, quei cortili, quei rifugi dai quali speriamo di non venire definitivamente sfrattati.

Anime in pena? No, piuttosto anime in transito, stupefatte e disorientate, ostinate nella loro permanenza terrena, sempre intente a ripetere gesti amati o solo abitudinari, talvolta con il rimpianto cocente di qualcuno che se n’è andato prima di loro. Oppure legati a luoghi, ad angoli, oggetti, anfratti specifici che hanno rappresentato un momento di svolta, di pura felicità o di angoscioso mutamento nella loro vita: la lavanderia di casa, con quel cestello che gira come un grande giocattolo, il teatro nel quale si è andati in scena tante volte, il letto nel quale distendersi accanto alla padrona, il telefono che continua a squillare nella notte senza che qualcun altro lo senta, un’agendina rossa, una fede nuziale e, naturalmente, urne cinerarie conservate in cima ad armadi e librerie e loculi e tombe amorevolmente accudite o dimenticate.

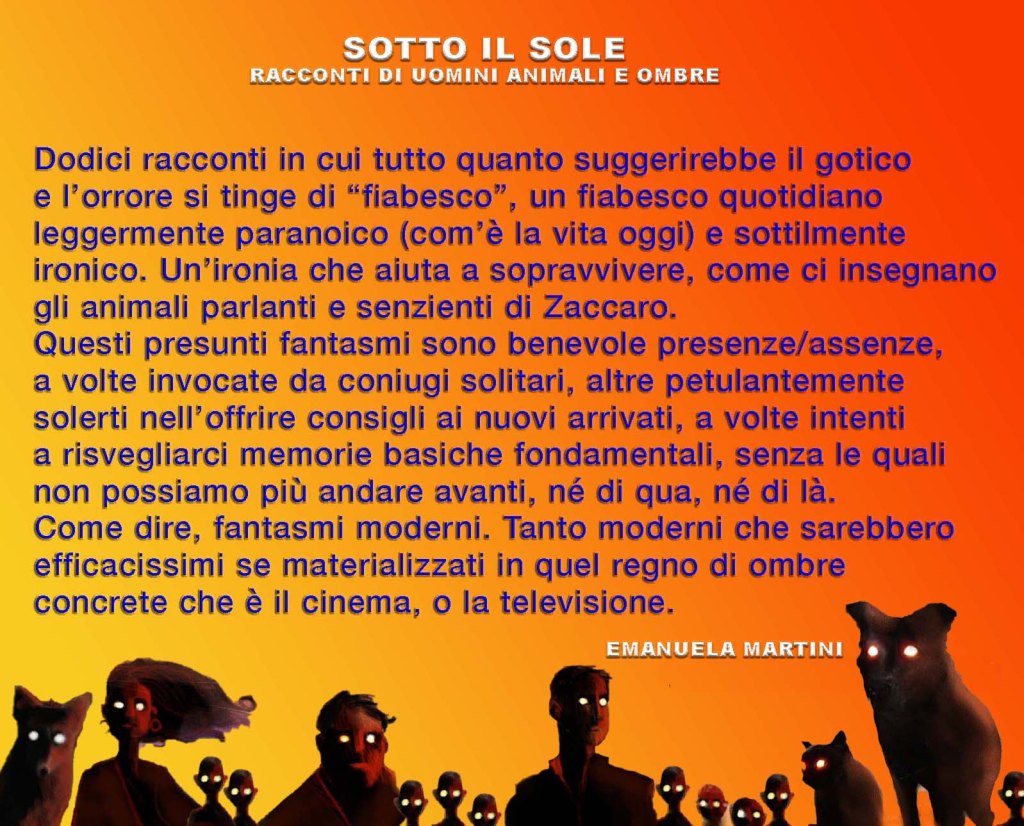

Ma in questi racconti tutto quanto suggerirebbe il gotico e l’orrore si tinge di “fiabesco”, un fiabesco quotidiano leggermente paranoico (com’è la vita oggi) e sottilmente ironico. Un’ironia che aiuta a sopravvivere, come ci insegnano gli animali parlanti e senzienti di Zaccaro. Questi presunti fantasmi sono benevole presenze/assenze, a volte invocate da coniugi solitari, a volte petulantemente solerti nell’offrire consigli ai nuovi arrivati, a volte intenti a risvegliarci memorie basiche fondamentali, sen- za le quali non possiamo più andare avanti, né di qua, né di là. Come dire, fantasmi moderni. Tanto moderni che sarebbero efficacissimi se materializzati in quel regno di ombre concrete che è il cinema (o la televisione).

Fu Henry James, probabilmente, a far compiere alla letteratura fantastica il salto definitivo dai furori romantici alle inquietudini novecentesche, non solo con il capolavoro Il giro di vite, ma con tutta la sua ricca, raffinata produzione di racconti fantastici; fu James (sulla scia di Nathaniel Hawthorne e, prima di lui, di E. T. A. Hoffmann) a collocare le sue ombre nel salotto e non in un torrione in rovina, a far apparire gli spettri delle sue dolenti governanti in pieno giorno in mezzo a un laghetto, a rivedere classiche iconografie, a rivelare altari dei morti tra le mura domestiche (non per niente, il padre di James era, oltre che filosofo, psicologo). Frantumando così i confini (e certe convenzioni narrative) tra “noi” e “loro” e ribaltando addosso a noi, al nostro confuso intimo e al peso inesprimibile del nostro passato, eventi e apparizioni singolari e apparentemente inspiegabili. Siamo noi i produttori di unheimlich e, come direbbe Todorov, è la nostra oscillazione perpetua tra il familiare e il non familiare che crea il fantastico. Dalla seconda metà del 900 gran parte della narrativa fantastica del mondo occidentale si è indirizzata soprattutto verso l’orrorifico, con le debite eccezioni naturalmente, compresi Stephen King (ma più il King non-horror di Stand By Me), gli Amabili resti di Alice Sebold (e il film che ne ha tratto Peter Jackson) o Il signor Diavolo (romanzo e film) di Pupi Avati, perdendo un po’ di vista quei misteri, quelle correnti d’aria, quelle impalpabili percezioni che noi e il nostro habitat produciamo. Più fruscii che luccicanze. Maurizio Zaccaro si muove in quella direzione, tenta di aprire uno spiraglio nella porta che noi pensiamo divida due mondi, ma che in realtà regola solo il flusso di due dimensioni sovrapposte e che si apre (e questo è ciò che davvero ci fa più paura) dentro di noi e dentro il nostro passato. E, una volta entrati, questi fantasmi indaffarati e chiacchieroni ci fanno compagnia.

Preface

Emanuela Martini

A lady in black with a bright red handbag and another in butter yellow, like the Queen of England, a retired widowed colonel, a pianist with a too-tight and somewhat threadbare tailcoat, a deejay who works on the radio at night, a country parish priest, and then couples who have been together all their lives and find it hard to part, and mothers and children with eyes as clear as water, unpredictable and visionary. And, along with the humans, many animals: a white cat with blue eyes, a black one with a pink ribbon on her head, an old Labrador with cataracts and a young puppy named Dan- te, a beige mouse and a fox with a big red tail: these are just some of the characters in the stories in Under the Sun – tales of humans, animals and shadows by Maurizio Zaccaro.

Busy in activities that are or, at times, “seem” normal, visible to all or some, outside and inside apartment buildings, supermarkets, farms, taverns, cemeteries, buses, by day as well as by night. Where do they go? Where do they come from? From what interstices of time and space do they emerge to cut us off, intertwine their lives with ours, speak to us, guide us? And, most importantly, what are they doing in our homes?

Here, houses (other major protagonists of these stories). Classic places in fantasy fiction (all of it, including film), which pass from hand to hand, from tenant to tenant, from owner to owner, preserving and handing down memories and traces, visible or invisible, of previous occupants. Houses that we don’t want to, or can’t, leave: otherwise where do the lady with the red purse, the cat Lea, the labrador Marietta go to live?

But, unlike what often happens, Zaccaro’s houses, whether bourgeois apartments or decayed country houses, are not malevolent, hostile, dangerous but, somehow, welcoming, consoling, “motherly.” Our home, our belongings, our soul. Of course, ours, but also those who lived there before. From these centuries-old cohabitations arise the entanglements between here and there, between living and dead, most pronounced and jarring, it is obvious, at the moment of passing, when our body stands on one side and we, detached from it, see it, and meanwhile meet new friends and “housemates,” those who were there before.

But let us go in order. Zaccaro’s tales begin, somewhat logically, in a funeral home, where the diminutive Emilio, a tanatopractor (the professional who takes care of the hygienic and aesthetic care of corpses before the funeral ceremony), is working on the body of his heterozygous twin brother, the corpulent Aurelio, who died by suicide. And here, unbeknownst to Emilio, Aurelio’s (and our) adventures in the shadow realm begin. Literal shadows, the ones we carry attached to us, who can be changeable and, at times, mischievous, but from whom, as E.T.A. Hoffmann teaches in The New Year’s Eve Tales, it is most dangerous to part. Hoffmann’s Tales, bizarre tales of wandering souls and shadows, eye merchants and seductive automatons come to life, all set in an everyday, concrete early 19th century, are certainly a source of inspiration for the author, who never strays from a plausible and usual visual range. But other “fathers” also hover around: Edgar Allan Poe, with his long-haired raven-haired or fragilely blond women; a few Rossettian-Peraphaelite suggestions, with deaths by drowning and swirling waters; touches of Aesopian wisdom; the tenderness of the saddest of classical fabulists; Hans Christian Andersen, who made his creatures, human, animal, hybrid, transit between different worlds. Even a tin soldier can have a heart and a life. Let alone animals, which here, as in all self-respecting fairy tales (however black), have very important roles. Not only in the first tale, but in many others, they are the conduit between dimensions, the ones who perceive the unknown, who “see” when we only feel a breeze of cold air, who wait for us when we join them “beyond” to help us adapt to the new condition. Playful as dogs, chatty as cats, they are indispensable presences of those apartments, those yards, those shelters from which we hope not to be permanently evicted. Souls in pain? No, rather souls in transit, stupefied and bewildered, obstinate in their earthly sojourn, always intent on repeating beloved or merely habitual gestures, sometimes with the bitter regret of someone who left before them. Or linked to specific places, corners, objects, nooks and crannies that represented a turning point, pure happiness or anguished change in their lives: the laundry room at home, with that basket spinning like a big toy, the theater in which one has gone on stage so many times, the bed in which to lie next to the mistress, the telephone that keeps ringing in the night without anyone else hearing it, a red diary, a wedding ring, and, of course, cinerary urns stored on top of closets and bookcases and burial niches and graves lovingly cared for or forgotten.

But in these tales everything that would suggest gothic and horror is tinged with “fairy tale,” an everyday fairy tale that is slightly paranoid (as life is today) and subtly ironic. An irony that helps one survive, as Zaccaro’s talking, sentient animals teach us. These supposed ghosts are benevolent presences/absences, sometimes invoked by lonely spouses, sometimes petulantly diligent in offering advice to newcomers, sometimes intent on awakening fundamental basic memories, without which we can no longer move forward, neither this way nor that. As it were, modern ghosts. So modern that they would be most effective if materialized in that realm of concrete shadows that is the cinema (or television).

It was Henry James, arguably, who made fantastic literature take the ultimate leap from Romantic fury to twentieth-century disquiet, not only with his masterpiece The Turn of the Screw, but with his entire rich, refined output of fantastic tales; it was James (in the wake of Nathaniel Hawthorne and, before him, E. T. A. Hoffmann) to place his shadows in the drawing room and not in a ruined keep, to make the ghosts of his sorrowful housekeepers appear in broad daylight in the middle of a pond, to revise classic iconographies, to reveal altars of the dead within the domestic walls (not for nothing, James’s father was, in addition to being a philosopher, a psychologist). Thus shattering the boundaries (and certain narrative conventions) between “us” and “them” and turning singular and seemingly inexplicable events and appearances back on us, on our confused inner selves and the inexpressible weight of our past. We are the producers of the unheimlich and, as Todorov would say, it is our perpetual oscillation between the familiar and the unfamiliar that creates the fantastic. Since the second half of the 20th century, much of the Western world’s fantastic fiction has turned mostly toward the horrific, with due exceptions of course, including Stephen King (but more the non-horror King of Stand By Me), Alice Sebold’s Lovable Remains (and the film Peter Jackson made of it) or Pupi Avati’s Mr. Devil (novel and film), losing a little sight of those mysteries, those draughts, those intangible perceptions that we and our habitat produce. More rustling than shimmering. Maurizio Zaccaro is moving in that direction, trying to open a crack in the door that we think divides two worlds, but which actually only regulates the flow of two overlapping dimensions and which opens (and this is what really scares us the most) inside us and inside our past. And, once inside, these busy, chattering ghosts keep us company.

ILLUSTRAZIONI DEL VOLUME:

ROBERTO BALLESTRACCI © 2022

Categorie

mauriziozaccaro Mostra tutti

Regista e sceneggiatore italiano.

Italian film director and screenplayer.