AUGUSTO TRETTI

Augusto Tretti, regista, racconta se stesso e i suoi film a una studentessa che ha l’ardire di fare una tesi su di lui. La scoperta della passione per il cinema, la benedizione di Filippo Sacchi, l’incontro con Fellini, ma soprattutto gli ostacoli del fare cinema nella totale autarchia.

Augusto Tretti, director, tells himself and his films to a student who has the audacity to do a thesis on him. The discovery of a passion for cinema, the blessing of Filippo Sacchi, the meeting with Fellini, but above all the obstacles of making films in total autarky.

Fonte: Film-Tv

«Lo si può, volendo, liquidare con due definizioni: goliardico, naïf. Alcuni lo fanno. Ma sono definizioni sbagliate. I gogliardi e i naïfs non hanno rigore, si fermano alle prime osterie, si divertono, riempiono le domeniche. Tretti non si diverte, benché sia difficile non divertirsi anche, vedendo i suoi film»

“One can, if one wishes, dismiss it with two definitions: goliardic, naïve. Some people do. But they are wrong definitions. Goliards and naïfs have no rigor, they stop at the first taverns, they have fun, they fill their Sundays. Tretti does not have fun, although it is hard not to have fun too, seeing his films.”

Ennio Flaiano

1984, Maurizio Zaccaro incontra Augusto Tretti, maestro misconosciuto del cinema italiano, nella sua villa nei pressi del Lago di Garda. Con loro una studentessa universitaria che sta scrivendo la tesi proprio su Tretti e che accompagna il regista ormai non più giovanissimo in lunghe passeggiate nella campagna e in visite ai luoghi in cui sono conservati i cimeli dei suoi film. Tretti parla in modo schietto, spesso tagliente e spassoso, dei suoi film, di come sia arrivato per caso al cinema e delle innumerevoli traversie produttive che ha dovuto affrontare per portare a compimento La legge della tromba e Il potere, le sue opere più famose.

1984, Maurizio Zaccaro meets Augusto Tretti, a misunderstood master of Italian cinema, at his villa near Lake Garda. With them is a university student who is writing her thesis precisely on Tretti and who accompanies the now-not-so-young director on long walks in the countryside and visits to places where memorabilia from his films are kept. Tretti speaks candidly, often cuttingly and hilariously, about his films, how he came to cinema by chance and the countless production travails he had to go through to bring to fruition The Law of the Trumpet and The Power, his most famous works.

33° TFF (Torino Film Festival)

Nota di Regia

Ho girato questo piccolo film nel 1984, per Ipotesi Cinema e Rai Uno. “Augusto Tretti, un ritratto” è dunque uno dei miei primissimi lavori. Sono trascorsi quarant’anni dalla sua realizzazione eppure l’ultima volta che sono passato da Colà (Lazise del Garda) poco prima della sua scomparsa ho provato le stesse sensazioni di allora. Varcare il portone della sua casa era come salire sulla macchina del tempo, talmente tutto era immutato. Gli oggetti, quelli che lui chiama con affetto “cimeli e ricordi”, dei pochi film che ha diretto nella sua carriera erano ancora lì come allora, così come era rimasto intatto, nel corso del tempo, l’arredo della villa. Nemmeno lui sembrava essere invecchiato, come se un efficace elisir gli avesse donato l’eterna giovinezza. Perché Augusto Tretti sostanzialmente era questo: un grande sognatore, come tutti i bambini. Intelligente, ironico, fantasioso, autore di cinema troppo scomodo e pungente, Augusto era una miniera d’idee. Stare con lui (come si può vedere in questo suo ritratto) voleva dire immergersi totalmente in un mondo fatto di racconti affascinanti e unici, di aneddoti esilaranti, di spunti e visioni che avrebbero potuto sfociare in film sorprendenti, e tanto altro ancora. Un mondo che in molti hanno poi liquidato come “goliardico” e “naif” . Eppure, per chi lo conosceva bene, di goliardico e naif Augusto non aveva proprio nulla. Da vero artigiano del cinema sapeva fare un po’ tutto, dall’operatore al montatore, dall’elettricista al costumista, allo scenografo e perfino l’attore. Non a caso, a Venezia nel 1972, per “Il potere” disse in conferenza stampa: “Ritengo che IL POTERE sia un film d’autore al cento per cento. Ho fatto tutto io, perfino il verso della gallina”. Purtroppo oggi pochi si ricordano di lui, dei suoi clamorosi film. Peccato. Ma Augusto è stato non solo un amico ma un “inventore” al quale ispirarsi per non morire di ovvietà, di banalità e soprattutto di omologazione. Non a caso Federico Fellini disse di lui: “Do un consiglio a tutti i miei amici produttori: acchiappate Tretti, fategli firmare subito un contratto, e lasciategli girare tutto quello che gli passa per la testa. Soprattutto non tentate di fargli riacquistare la ragione; Tretti è il matto di cui ha bisogno il cinema italiano”. Oggi, di matti nel cinema italiano non ce ne sono più. Sono stati fatti sparire tutti, uno dopo l’altro. Fermati, radiati, dimenticati. E il nostro cinema soffre della loro assenza. Lunga vita dunque a LA LEGGE DELLA TROMBA, a IL POTERE, a ALCOOL: i tre indimenticabili, graffianti capolavori di Augusto Tretti, “anarchico di linea veronese”, come lui stesso amava definirsi.

Maurizio Zaccaro

Director’s note

I made this small film in 1984, for Ipotesi Cinema and Rai Uno. “Augusto Tretti, a portrait” is thus one of my very first works. More than 40 years have passed since it was made, and yet the last time I passed through Colà (Lazise del Garda) shortly before his passing, I felt the same feelings as then. Stepping through the door of his house was like stepping into a time machine, so unchanged was everything. The objects, what he fondly calls “heirlooms and mementos,” from the few films he directed in his career were still there as they were then, just as the furnishings of the villa had remained intact over time. He did not seem to have aged either, as if an effective elixir had given him eternal youth. For Augusto Tretti basically was this: a great dreamer, like all children. Intelligent, ironic, imaginative, an author of too uncomfortable and pungent cinema, Augusto was a mine of ideas. To be with him (as can be seen in this portrait of him) was to be totally immersed in a world of fascinating and unique tales, hilarious anecdotes, insights and visions that could have resulted in amazing films, and so much more. A world that many later dismissed as “goliardic” and “naive” . Yet, for those who knew him well, goliardic and naive Augustus had nothing at all. As a true craftsman of cinema he could do a little bit of everything, from cameraman to editor, electrician to costume designer, set designer and even actor. Not surprisingly, at Venice in 1972, for “The Power,” he said at a press conference, “I consider THE POWER to be a 100 percent auteur film. I did everything, even the chicken verse.” Unfortunately, few people today remember him, his resounding films. Too bad. But Augusto was not only a friend but an “inventor” to be inspired by in order not to die of obviousness, banality and above all homologation. It is no coincidence that Federico Fellini said of him, “I give a piece of advice to all my producer friends: catch Tretti, get him to sign a contract right away, and let him shoot whatever comes into his head. Above all, do not try to make him come to his senses; Tretti is the madman that Italian cinema needs.” Today, there are no more lunatics in Italian cinema. They have all been disappeared, one after another. Stopped, disbarred, forgotten. And our cinema suffers from their absence. So long live LA LEGGE OF THE TRUMP, THE POWER, ALCOHOL: the three unforgettable, biting masterpieces of Augusto Tretti, “an anarchist of the Veronese line,” as he liked to call himself.

Foto di Maurizio Zaccaro © 1978

«Do un consiglio a tutti i miei amici produttori: acchiappate Tretti, fategli firmare subito un contratto, e lasciategli girare tutto quello che gli passa per la testa. Soprattutto non tentate di fargli riacquistare la ragione; Tretti è il matto di cui ha bisogno il cinema italiano». Parola di Federico Fellini, uno dei grandi maestri del cinema italiano che salutò con ammirazione l’esordio, assolutamente autarchico (prima di Moretti…), di Augusto Tretti, il più originale e stravagante regista italiano. La sua carriera, racchiusa in un pugno di film (3 e ½: La legge della tromba, Il potere, il film su commissione Alcool e il cortometraggio per la Rai Mediatorie carrozze), si dispiega in un lasso di tempo molto ampio, 25 anni (e anche oltre, se consideriamo i progetti non realizzati). Tutto ha inizio nel 1960, quando il giovane regista, con la copia del suo primo film in mano, La legge della tromba, cala a Roma e organizza una proiezione per la critica. Riceve giudizi per una volta unanimi, ovviamente negativi, ma per sua fortuna Moravia lo invita a far vedere il film ai registi, non ai critici. Grazie a questa intuizione dello scrittore esplode a Roma il caso Tretti, un marziano sceso dal Veneto (Tretti è nato a Verona nel 1924) nel mondo dei cinematografari e subito adottato da Fellini, Flaiano, Antonioni, Tonino Guerra e molti altri, che si prodigano per consentirgli di girare un film con una struttura produttiva alle spalle. La Titanus addirittura, grazie a Goffredo Lombardo, che dopo aver accettato di distribuire La legge della tromba («Questo film lo piglio io, lo mando a Milano e se non vogliono compro il locale»), fa firmare al regista un contratto per un nuovo film. Ha inizio da questo momento una delle più lunghe avventure produttive del cinema italiano, perché il secondo film di Tretti, Il potere, vedrà la luce solo dieci anni dopo, a causa del fallimento della Titanus e ad altre vicissitudini. Inizio e fine di una carriera, ispirata da una passione sfrenata per il cinema e da un talento che solo i geni del cinema italiano hanno saputo veramente apprezzare. L’invito alla visione è questa volta rivolto proprio ai critici e agli storici, affinché il nome di Tretti possa trovare il posto che merita nella storia del cinema italiano.

“I give a piece of advice to all my producer friends: catch Tretti, get him to sign a contract right away, and let him shoot whatever comes into his head. Above all, don’t try to make him come to his senses; Tretti is the madman that Italian cinema needs.” The words of Federico Fellini, one of the great masters of Italian cinema who greeted with admiration the absolutely autarkic (before Moretti…) debut of Augusto Tretti, Italy’s most original and quirky director. His career, encapsulated in a handful of films (3 ½: The Law of the Trumpet, The Power, the commissioned film Alcohol and the short film for Rai Mediatorie carrozze), unfolds over a very wide time span, 25 years (and even more, if we consider the unrealized projects). It all begins in 1960, when the young director, with a copy of his first film in hand, The Law of the Trumpet, descends on Rome and organizes a screening for critics. He receives unanimous reviews for once, obviously negative, but fortunately for him Moravia invites him to let the filmmakers, not the critics, see the film. Thanks to this intuition of the writer, the Tretti case explodes in Rome, a Martian who came down from the Veneto (Tretti was born in Verona in 1924) into the world of filmmakers and was immediately adopted by Fellini, Flaiano, Antonioni, Tonino Guerra and many others, who did their best to allow him to make a film with a production structure behind it. Titanus even, thanks to Goffredo Lombardo, who after agreeing to distribute La legge della tromba (“I’ll take this film, I’ll send it to Milan and if they don’t want to I’ll buy the place”), makes the director sign a contract for a new film. From this moment begins one of the longest production adventures in Italian cinema, because Tretti’s second film, Il potere, will only see the light of day ten years later, due to the bankruptcy of Titanus and other vicissitudes. Beginning and end of a career, inspired by an unbridled passion for cinema and a talent that only the geniuses of Italian cinema were able to truly appreciate. The invitation for viewing is this time addressed precisely to critics and historians, so that Tretti’s name may find the place it deserves in the history of Italian cinema.

Filmografia:

La legge della tromba (1960) Regia: Augusto Tretti; soggetto e sceneggiatura: A. Tretti; musica: Angelo Paccagnini, Eugenia Manzoni Tretti; montaggio: Mario Serandrei; interpreti: Maria Boto, A. Paccagnini, E. Manzoni Tretti; origine: Italia; produzione: A. Tretti; durata: 75′ Un gruppo di amici tentano di compiere una rapina, ma vengono arrestati. Amnistiati, ottengono un poso di lavoro in una fabbrica di trombe… «La legge della tromba è il film più strabiliante che abbia mai visto, il più fuori dal comune» (Vancini); «Vengono in mente le fantasie di Charlot, i films di Tati, intere sequenze sono rette da un miracoloso equilibrio di ironia e di lirismo» (Zurlini); «In questo giovane e nel suo film c’è estro da vendere» (Antonioni); «È una piccola lezione di cui ammiro il candore e l’astuzia» (Flaiano).

LA LEGGE DELLA TROMBA – The Law of the Trumpet (1960) Director: Augusto Tretti; subject and screenplay: A. Tretti; music: Angelo Paccagnini, Eugenia Manzoni Tretti; editing: Mario Serandrei; performers: Maria Boto, A. Paccagnini, E. Manzoni Tretti; origin: Italy; production: A. Tretti; running time: 75′. A group of friends attempt a robbery, but are arrested. Amnestied, they get a job position in a trumpet factory…. “The Law of the Trumpet is the most mind-blowing film I have ever seen, the most out of the ordinary” (Vancini); ‘Charlot’s fantasies come to mind, Tati’s films, entire sequences are held up by a miraculous balance of irony and lyricism’ (Zurlini); ‘In this young man and in his film there is inspiration to spare’ (Antonioni); ‘It is a small lesson whose candor and astuteness I admire’ (Flaiano).

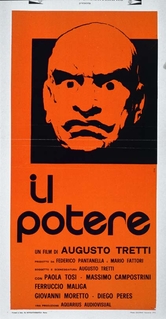

Il potere (1971) Regia: Augusto Tretti; soggetto e sceneggiatura: A. Tretti; scenografia: Giuseppe Raineri; musica: Eugenia Manzoni Tretti; montaggio: Giancarlo Raineri; interpreti: Paola Tosi, Massimo Campostrini, Ferruccio Maliga, Giovanni Moretto, Diego Peres, A. Tretti; origine: Italia; produzione: Aquarius Audiovisual; durata: 83′ «Il potere è una rappresentazione didattica e grottesca della tirannia attraverso i secoli, dall’età della pietra a oggi: rivisita l’antica Roma, gli stermini perpetrati a danno dei pellerossa, il fascismo e gli anni che prelusero alla dittatura mussoliniana. Non c’è trama e non è il caso di dolersene. Sono ricchi a tener banco e a menar randellate sulla povera gente e sui suoi difensori […]. Il potere è un’opera di poesia, che dell’assunto politico fa la base per la realizzazione di una straordinaria “commedia dell’arte” cinematografica, la prima, forse, commedia dell’arte che possa ricordarsi nella storia del cinema italiano» (Bendazzi).

IL POTERE – The Power (1971) Director: Augusto Tretti; subject and screenplay: A. Tretti; set design: Giuseppe Raineri; music: Eugenia Manzoni Tretti; editing: Giancarlo Raineri; actors: Paola Tosi, Massimo Campostrini, Ferruccio Maliga, Giovanni Moretto, Diego Peres, A. Tretti; origin: Italy; production: Aquarius Audiovisual; duration: 83′ “Power is a didactic and grotesque portrayal of tyranny through the centuries, from the Stone Age to the present: it revisits ancient Rome, the exterminations perpetrated against the Native Americans, fascism and the years leading up to the Mussolini dictatorship. There is no plot and no cause for grief. It is rich people who hold sway and bludgeon the poor people and their defenders […]. Il potere is a work of poetry, which makes the political assumption the basis for the creation of an extraordinary cinematic ‘commedia dell’arte,’ the first, perhaps, commedia dell’arte that can be remembered in the history of Italian cinema” (Bendazzi).

Il potere

(Ennio Flaiano / pubblicata su «L’Espresso» il 14 novembre 1971)

Negli scaffaloni della cinematografia italiana, Augusto Tretti, coi suoi due film, «La legge della tromba» e «Il potere» (due film in dieci anni, e il primo mai visto, se non da pochi amici), è difficile da collocare. Bisogna rinunciarvi. Resterà un fenomeno isolato o, peggio, da isolare. Forse avrà, in questo paese di manieristi, degli imitatori, ma sicuramente goffi o soltanto furbi. Il dono di Tretti è una semplicità che non si copia, presuppone la superba innocenza dell’eremita. E’ una semplicità che riporta l’immagine fotografica alle composizioni di Nadar, di Daguerre, e anche al non-realismo, cioè agli spazi e al nitore dell’affresco. Eppure Tretti non è un esteta, né chiede all’immagine se non di sostenere un suo elementare discorso. Lo si può, volendo, liquidare con due definizioni: goliardico, naif. Alcuni lo fanno. Ma sono definizioni sbagliate. I goliardi e i naifs non hanno rigore, si fermano alle prime osterie, si divertono, riempiono le domeniche. Tretti non si diverte, benché sia difficile non divertirsi anche, vedendo i suoi films. Egli ha fatto sua la lezione di Brecht, ma la svolge senza grandi apparati e con estro vernacolo. Il suo discorso è «papale papale», come si diceva una volta a Roma, cioè franco, diretto. La sua comicità è veneta, se si pensa al Ruzzante e ai suoi attori presi dalla strada (ma, intendiamoci, proprio strada, di paese e di campagna), e dalle osterie. E’ fantastica, iperletteraria, se si pensa ad Alfred Jarry. Altri nomi non suggerisce. Bisogna accettarlo e tener presente che niente in lui è ingenuo o copiato, ma viene da una cultura ben digerita, strizzata alla radice, e da un naturale apparentemente benevolo. Non lascia niente al caso. La ricerca della bellezza, dell’effetto, che rovina tanti nuovi autori e li spinge continuamente a cercare salvezza nel kitsch del giorno, (nel criptokitsch), cioè nelle immagini dettate dalla moda, dal vento che tira, dalle esperienze riuscite degli altri, dalla loro presunzione di registi che «vedono bene», è in Tretti una ricerca della cosa essenziale, adrammatica, messa in vitro e osservata alla macchina da presa, che diventa una specie di microscopio. Si potrebbe citare anche Hogarth per certi effetti di pomposità caricaturale, ma è meglio non farlo. I suoi personaggi non sono mai burattini, esistono nel momento in cui si realizzano e ritornano sotto altre vesti al momento opportuno. Per ritrovare certe immagini grottesche del fascismo, la sua complessa stupidità, credo che potrebbe soccorrerci soltanto Mino Maccari.

Tretti fa un cinema didascalico da sillabario, vuol dire una sua idea della società, e perché non gli piace. Ci riesce per una sua forza derisoria che si avvale d’impassibilità, di non-compiacimento. I volti esemplari, il modo di muoversi, la solitudine dei suoi attori (folle di otto persone, eserciti di dodici soldati), riportano il cinema a un eden dimenticato; a grandi spazi fatti di paesi, monti e campagne della memoria. Quando vuol colpire lo fa con la rapidità dell’evidenza. Si serve di un discorso volutamente dimesso perché ha le idee chiare. E’ anche difficile collocarlo nello scaffale di sinistra. Egli si ritiene anarchico, di linea veronese, cioè un po’ folle. Le sue bombe scoppiano con un enorme rispetto della vita umana, ma non a vuoto.

Alla mostra di Venezia si è presentato, contro il parere dei suoi molti amici e sostenitori, perché da dieci anni c’era un pubblico, ha bisogno del controllo di un pubblico. Risultato: il successo del «Potere» è stato imprevisto e chiaro: applausi ai due spettacoli. All’Arena, due minuti precisi di applausi. Tretti li ha cronometrati. Il giudizio che pesava su di lui, di non tener conto delle leggi dello spettacolo, di non essere di nessuna corrente, è caduto; anche (e forse soprattutto) se qualche critico lo ha trattato come un caso divertente, con l’affetto che si riserva agli innocui.

Per fare «Il potere», Tretti ha impiegato sette anni, di cui sei senza far niente, solo pensare al suo film, essendo venuto a mancare di colpo il produttore. Ha vissuto per sei anni con le bobine del suo film incompiuto sotto il letto. Infine ha trovato due produttori che gli hanno permesso di terminarlo. Ma un film finito non è necessariamente un film vivo: ha bisogno di essere «distribuito», visto, discusso. Penso che se questo film (e me lo auguro) arriverà nelle sale comuni – e non sarà quindi costretto a fare il giro dei festival, come numero di attrazione naif – impressionerà il pubblico per le sue qualità di feroce e austera comicità. •

Ennio Flaiano

(Ennio Flaiano / published in “L’Espresso” on November 14, 1971)

On the shelves of Italian cinematography, Augusto Tretti, with his two films, “The Law of the Trumpet” and “The Power” (two films in ten years, and the first one never seen except by a few friends), is difficult to place. It must be given up. It will remain an isolated phenomenon or, worse, to be isolated. Perhaps he will have, in this country of mannerists, imitators, but surely clumsy or merely cunning. Tretti’s gift is a simplicity that cannot be copied; it presupposes the superb innocence of the hermit. It is a simplicity that brings the photographic image back to the compositions of Nadar, Daguerre, and even to non-realism, that is, to the spaces and clarity of the fresco. Yet Tretti is not an aesthete, nor does he ask the image except to support an elementary discourse of his own. One can, if one wishes, dismiss him with two definitions: goliardic, naive. Some do. But they are wrong definitions. Goliards and naifs have no rigor, they stop at the first taverns, they have fun, they fill their Sundays. Tretti does not have fun, although it is hard not to have fun too, seeing his films. He has made Brecht’s lesson his own, but he carries it out without great apparatus and with vernacular flair. His speech is “papal papal,” as they used to say in Rome, that is, frank, direct. His comedy is Venetian, if you think of Ruzzante and his actors taken from the street (but, mind you, just street, village and country), and from taverns. It is fantastic, hyperliterary, if one thinks of Alfred Jarry. Other names it does not suggest. One has to accept it and keep in mind that nothing in him is naive or copied, but comes from a well-digested culture, wrung out at the root, and a seemingly benevolent natural. He leaves nothing to chance. The search for beauty, for effect, which ruins so many new authors and continually drives them to seek salvation in the kitsch of the day, (in cryptokitsch), that is, in images dictated by fashion, by the wind that blows, by the successful experiences of others, by their presumption as filmmakers who “see right,” is in Tretti a search for the essential, adramatic thing, put in vitro and observed at the camera, which becomes a kind of microscope. One could also cite Hogarth for certain effects of caricatured pomposity, but it is better not to do so. His characters are never puppets; they exist in the moment of realization and return in other guises at the appropriate time. To rediscover certain grotesque images of fascism, its complex stupidity, I think only Mino Maccari could help us. Tretti makes didactic syllabary cinema, means his own idea of society, and why he does not like it. He succeeds by a derisive force of his own that makes use of impassivity, of non-complacency. The exemplary faces, the way they move, the loneliness of his actors (crowds of eight, armies of twelve soldiers), take the cinema back to a forgotten Eden; to great spaces made up of villages, mountains and the countryside of memory. When he wants to strike, he does so with the swiftness of evidence. It uses deliberately dim speech because it has clear ideas. It is also difficult to place him on the leftist shelf. He considers himself to be an anarchist, of the Veronese line, that is, a bit crazy. His bombs go off with tremendous respect for human life, but not empty.

At the Venice exhibition he showed up, against the advice of his many friends and supporters, because for ten years there was an audience, he needs the control of an audience. Result: the success of “Power” was unexpected and clear: applause at the two shows. At the Arena, two precise minutes of applause. Tretti timed them. The judgment that weighed on him, of disregarding the laws of entertainment, of being of no current, fell away; even (and perhaps especially) if some critics treated him as a funny case, with the affection reserved for the harmless. To make “The Power,” Tretti took seven years, six of them doing nothing, just thinking about his film, the producer having suddenly passed away. He lived for six years with the reels of his unfinished film under his bed. Finally he found two producers who allowed him to finish it. But a finished film is not necessarily a living film: it needs to be “distributed,” seen, discussed. I think that if this film (and I hope so) makes it to common theaters-and thus is not forced to make the festival rounds as a naive attraction act-it will impress audiences with its qualities of fierce, austere comedy. –

Alcool (1979) Regia: Augusto Tretti; soggetto e sceneggiatura: A. Tretti; musica: Eugenia Manzoni Tretti; interpreti: Mario Graziosi e attori non professionisti; origine: Italia; produzione: A. Tretti per l’Amministrazione Provinciale di Milano; durata: 100′ «L’idea di un film sull’alcoolismo nacque da un mio colloquio col professor Dario De Martis [Direttore dell’Istituto Psichiatrico di Pavia]. […] Scartai subito l’idea del film-inchiesta perché troppo facile e insoddisfacente dal punto di vista artistico, sforzandomi di filtrare i vari aspetti del problema in un film d’autore. Ho cercato di affrontare il tema con la maggior chiarezza e semplicità possibile, senza nascondermi dietro l’intellettualismo a ogni costo. […] Trattandosi di un film culturale, mi sono sforzato di conciliare la mia natura satirica con gli aspetti più apertamente didascalici del tema» (Tretti). «È un film, che si impernia sul personaggio di un fattorino che a furia di vedersi offrire il classico “bianchino” da ogni cliente, finisce per diventare un alcolizzato impenitente, è spesso francamente spassoso, soprattutto quando il regista parte dal “discorso sull’alcool” per disegnare quadri satirici di incredibile efficacia» (Crespi).

Alcool (1979) Director: Augusto Tretti; subject and screenplay: A. Tretti; music: Eugenia Manzoni Tretti; performers: Mario Graziosi and non-professional actors; origin: Italy; production: A. Tretti for the Provincial Administration of Milan; running time: 100′ “The idea of a film on alcoholism arose from a conversation I had with Professor Dario De Martis [Director of the Psychiatric Institute of Pavia]. […] I immediately discarded the idea of a film-investigation because it was too easy and unsatisfactory from an artistic point of view, striving to filter the various aspects of the problem into an art film. I tried to approach the subject with as much clarity and simplicity as possible, without hiding behind intellectualism at any cost. […] Since this is a cultural film, I made an effort to reconcile my satirical nature with the more overtly didactic aspects of the theme” (Tretti). “It is a film, which hinges on the character of a bellboy who, by dint of being offered the classic “bianchino” by every customer, ends up becoming an unrepentant alcoholic, is often frankly hilarious, especially when the director starts from the “discourse on alcohol” to draw satirical pictures of incredible effectiveness” (Crespi)-

Mediatori e carrozze (1985)

Regia: Augusto Tretti; soggetto e sceneggiatura: A. Tretti; fotografia: Maurizio Zaccaro; montaggio: M. Zaccaro; produzione: Società Editoriale G.B. Verci di Bassano per Rai 1; durata: 18′

Un insegnante di provincia si rivolge a un agente immobiliare per acquistare una casa, ma a causa al boom edilizio molti si sono improvvisati mediatori e non sempre i consigli sono quelli giusti… Il film è stato realizzato per la serie televisiva Di paesi e città.

Mediators and Carriages (1985)

Director: Augusto Tretti; subject and screenplay: A. Tretti; photography: Maurizio Zaccaro; editing: M. Zaccaro; production: Società Editoriale G.B. Verci di Bassano for Rai 1; running time: 18′

A provincial teacher turns to a real estate agent to buy a house, but due to the housing boom many have improvised as brokers and the advice is not always the right one… The film was made for the TV series Di paesi e città.

Verona, 19 giugno 1924 – Verona, 7 giugno 2013

Categorie

mauriziozaccaro Mostra tutti

Regista e sceneggiatore italiano.

Italian film director and screenplayer.